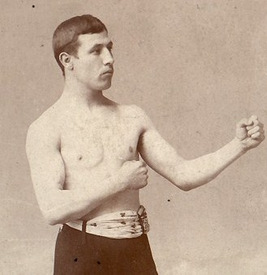

by Matt McGrain: When George McFadden passed away on May the 6th, 1951 Nat Fleischer, writing in Ring magazine, called him “a champion in any other era”. And that was pretty much it for George. Nobody has really had very much to say about this pioneering lightweight since his death. But in 1899, “Elbows” McFadden matched a true ring legend no less than three times – all over the scheduled distance of 25 rounds. These three duels, separated as they were by only a little more than six months, should be enough to seal his place in ring lore, but McFadden also found time to match the two other outstanding lightweights of perhaps the greatest era in the history of arguably the deepest division of all, champions Kid Lavigne and Frank Erne.

by Matt McGrain: When George McFadden passed away on May the 6th, 1951 Nat Fleischer, writing in Ring magazine, called him “a champion in any other era”. And that was pretty much it for George. Nobody has really had very much to say about this pioneering lightweight since his death. But in 1899, “Elbows” McFadden matched a true ring legend no less than three times – all over the scheduled distance of 25 rounds. These three duels, separated as they were by only a little more than six months, should be enough to seal his place in ring lore, but McFadden also found time to match the two other outstanding lightweights of perhaps the greatest era in the history of arguably the deepest division of all, champions Kid Lavigne and Frank Erne.

Elbows also fought eight times outside of the highest class, going unbeaten and scoring five knockouts, but it is the story of his battles with Gans, Lavigne and Erne that I want to tell here, battles that saw McFadden matched to a higher class in a single year than perhaps any other fighter – ever. Doing so is never easy with no footage of Elbows thought to be in existence, but hopefully we can even learn a thing or two about the style of possibly the most modern fighter of his generation, beginning with the fight that was an enormous step up in class for Elbows, who was described before his first duel with Gans as being “a practical newcomer to the upperdom of the fistic art”. It’s was a fair point with George listed at 20-3-12 by Boxrec at this stage to Joe’s 68-4-8.. “The Old Master” was yet to gather the years to have earned the first part of that nickname, but aged twenty-five he was very much a master, unbeaten in twenty-six tries and negotiating the twenty-five round distance twice in the previous year, something George had yet to do. He would also be out-weighed, giving up 6lbs to a fighter capable of beating much bigger men. The odds were against an Elbows victory.

“McFadden gave the most remarkable display of blocking ever seen in a local ring,” trumpeted The Saint Paul Globe the following morning, “Gans tried in every way to get in on the New Yorker, but was invariably stopped. If McFadden blocked with his left he sent his right to the body and sent the left to the face.” Elbows was unquestionably a defensive specialist, and he employed his elbows to protect the body and head. This, for the time, was a unique style, unique enough to earn George “Elbows” McFadden his nickname (though he was also a little naughty with these celebrated appendages) and it may also have been more modern than any of his peers, hands up, elbows tucked into the ribs. But George’s guard was a mobile one: “My elbows ensured their fists stayed away from my chin” as he would put it. This brings to mind the cross-arm guard of some of the 1940’s legends, men like Archie Moore. Elbows was an in-fighter and a counter-puncher, so like Moore a fluid cross-arm guard deployed out of a crouch at close quarters makes sense – of course we will never know, but what can be said without fear of contradiction is that he fought with a specialised style that brought great success – because McFadden beat Gans in this, their first meeting, on April 4th 1899.

After a typically slow start, “McFadden cut loose, took a lead, and was never again headed.” Keeping the fight up close without being tempted into leading to often, Gans forced the great boxer in the fight to work at pace, all the while countering to the body so that “at the close of the 18th round Gans was very tired and groggy”. Keeping the pressure on, but repeatedly letting Gans of the hook, McFadden had to wait until the 23rd round to do what no man had ever done before, and something that arguably did not legitimately occur again until the very twilight of The Old Master’s career some 9 years later – he knocked Joe Gans out. “McFadden opened the 23rd round with two rights to the body and a left to the face, Gans was manifestly distressed. Suddenly, the white lad sent in his right to the jaw and then hooked his left on the chin. Gans toppled over and was unable to rise.”

The splendour of this achievement cannot be overstated. Gans would be stopped by Erne on a cut caused by an apparently accidental head-butt in 1900, suffered the dubious second round stoppage versus Terry McGovern a few months later and was knocked out by all-time great Battling Nelson twice in his final months as a pro, but McFadden, relatively green as he was, is the only man to hold a clean controversy free KO over Joe Gans in his prime.

After resting on his laurels for less than one month, Elbows stepped in with Frank Erne, once more in New York. Erne was a superb boxer and excellent puncher, who had fought world champion Kid Lavigne to a draw less than a year earlier and was unbeaten since George Dixon, another great fighter, had separated him from his featherweight title in March of 1897. Furthermore, this was a title Erne had earned by beating Dixon in November of 1896. The fight was desperately close, but Erne had beaten Dixon with boxing – in short, he had out-boxed perhaps the best boxer the ring had seen in the years before Joe Gans. McFadden once again had his work cut out for him.

It was another desperately close fight and, as against Dixon, Erne did just enough to get the decision. McFadden once again started slowly and in the first three rounds Erne was “all over his man”. McFadden came alive in the fourth, “blocking beautifully and countering with a right hand to the heart”. Moving his counterpunches to the head in the 8th, McFadden cut Erne’s eye and then proceeded to target the cut with hard rights. “In the ninth, McFadden placed his left repeatedly on the damaged optic, and did beautiful execution in blocking Erne’s leads.” McFadden continued to dominate through the 11th, but in the 12th Erne came roaring back into the fight, bossing the fight into the 15th when a brutal exchange seemed to end his period in charge. After this, they fought each other carefully, Erne working behind a jab which would eventually bring blood from McFadden’s nose, whist George continued to block and counter to the body. In the 22nd the men put on “a beautiful exhibition of lightning drives and beautiful blocking” with each “judging the distance so carefully that little damage was done“. But right at the end of the round, Erne may have settled the fight in his favour, as McFadden “received a jolt to the jaw which sent him to the floor”. Rising at once, McFadden put on a brilliant display of blocking to see out the round but he appears to have dropped the 24th, and whilst he may have won the 25th and final round, Erne was given the decision by the referee in a fight that one newspaper claimed “rends like a draw”.

Even an ex-champion will often look to a soft option after a damaging loss – but just over two months after losing to Erne, George stepped back into the ring with Joe Gans.

This fight was much closer and “although pretty, was not decisive”. McFadden worked the body hard but seems to have been beaten to the punch by Gans, who tried to stay on the outside more, jabbing and hooking. Gans here began the slow and painful process of uncovering McFadden’s greatest weakness – he relied heavily on certain punches in offence. He led to the body and tended to jab the gut, moving upstairs with that punch more rarely; when he led with his right, which was often, he also favoured bodywork, and he tended to follow it up with a left to the jaw or a clinch. His defensive genius meant that in his prime, he would never be out of any fight altogether, and he seemed to have the ability to box or brawl so he would never have been entirely at a loss for a plan of action, but the list of punches that an opponent needed to neutralise was short. Here, trying the same tricks as he had for 23 rounds versus Gans in their previous outing, he found himself unable to repeat that success – and having perhaps been unlucky not to get the draw against Erne, here he was here lucky to be awarded one, although he did pull out all the stops in an astonishing last round, fighting a stunned Gans “to a standstill”.

Gans finished the job he started in this second fight almost exactly three months later in the pair’s third meeting of the year, finally out-pointing McFadden over the 25 round distance, but only after “one of the hardest fights witnessed at the [Broadway Athletic Club, Brooklyn] in a long time”. McFadden fought one of his most aggressive fights but in spite of great success to the body he was firmly out-boxed by Gans who, repeatedly tagged McFadden flush, “but McFadden seemed to be made of iron, and refused to be put out”. Gans had finally solved the McFadden problem, and he would not let him off the hook; although McFadden would fight Gans to another draw, and to a no contest, he would also lose two fights, one by brutal technical knock-out. But that would be three years later. In 1899 Elbows had proven himself an iron man, perhaps even one who could not be knocked out – and he had shown this to an even greater extent only twenty-five days before the third Gans fight, when, in the same venue, he had destroyed deposed champion Kid Lavigne.

Lavigne was a massive lightweight, short in stature but built like the tank he emulated in the ring. Described by McFadden himself as “the gamest man I ever fought” his speed, durability and ruggedness were exceeded only by the reputation of his power. “He hit like a heavyweight…the hardest hitting lightweight the ring has ever seen” remembered George in a rare surviving interview from 1925. “I thought I could slug with him” offered up the iron-chinned defensive master. “Two left hooks to my body convinced me I was wrong so I proceeded to change my tactics”. Boxing carefully, McFadden was forced onto the back foot as Lavigne “tore after me with all his famed fury”. Lavigne hit George so hard upon his right elbow that it became swollen to the point where he couldn’t put on his jacket post-fight. “The top of my head was the only unprotected spot on my body. He came down on the crown of my head with his right like a ton of bricks. The blow, it is strange to say, didn’t seem to dull my senses any. Only I seemed to be walking on air for the rest of the fight. It was a peculiar sensation. My head felt like a balloon.”

Early in the seventeenth round “he got over a beautiful right hand to my chin. My legs trembled, but I repelled with a short right to the former champion’s head. It dropped him for three. That was the punch which really beat The Kid.” Lavigne soldiered on as far as the 19th when he was dropped five times before being counted out at the sixth time of asking. It was the first and only time in his storied career that Lavigne would hear the count of ten.

Elbows McFadden was an unusual stylist with a big punch, a huge heart, an iron jaw and perhaps the most celebrated defence of his era. In 1899 he matched three men who would continue to be celebrated down the years as fighters in a way that has not been true of the little known McFadden. Why is this? Perhaps primarily, he was never the champion. But a quick look at the time line tells us just how unlucky he was in this. In April he beat Joe Gans, and although he would fight the great man for the title years later, Gans was not in possession of the championship at this time. The champion was Kid Lavigne. Kid Lavigne would lose his title that year – to one Frank Erne. Frank Erne got this title shot by virtue of his win over Elbows – a win which, it seems, perhaps could have been rendered a draw. Had the draw been the result, would Elbows have been given the nod against Lavigne by virtue of his KO of Gans? It seems likely. And in Lavigne’s very next fight after his losing the title, he was stopped in that brutal showing against McFadden.

In short, McFadden beat the future champion, the deposed champion, and dropped the narrowest of decisions to the very next champion, all within six months of each other. As Nat Fleischer said – “a champion in any other era” – but apparently not fit for the International Boxing Hal of Fame in this one.