By Mike Casey – There was that famous first fight between the two masters, and the fight before that with which many boxing fans of today might not be familiar. Before Benny Leonard figured out Freddie Welsh and took away his lightweight championship, Freddie had figured out Benny. It is so often the way it goes between two titans who are thrown together in the same little pocket of time.

By Mike Casey – There was that famous first fight between the two masters, and the fight before that with which many boxing fans of today might not be familiar. Before Benny Leonard figured out Freddie Welsh and took away his lightweight championship, Freddie had figured out Benny. It is so often the way it goes between two titans who are thrown together in the same little pocket of time.

Both men were geniuses of their profession, and I don’t describe them thus lightly. The once prized word of ‘genius’ has sadly lost much of its gloss in our super/brilliant/fantastic 24/7 era of eternal blue sky thinking. We like to think that geniuses come strolling down the trail every five minutes because it shields us from the uncomfortable fact that most of today’s ‘world champions’ fall woefully short of the mark. Boxing geniuses, for one thing, know how to throw a left jab properly.

Most of us, I hope, appreciate the genius of Benny Leonard, although I have encountered a few starry-eyed souls who have told me that Benny would have been sent packing by Floyd Mayweather Jnr. But how many know of Freddie Welsh and all his glorious fistic and social contradictions?

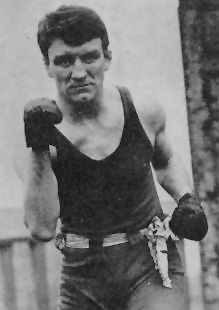

Pale and lean as a greyhound, Freddie was a fascinating conundrum in and out of the ring. Born in Pontypridd, Wales, he grew to be a master boxer, a brilliant exponent of the left jab and equally adept at scrapping and spoiling in the trenches. He could make hearts soar with the elegance and cleverness of his work or he could severely test the patience of his audience by cynically shutting his opponent down with artfully executed fouls and general negativity.

That lively and intelligent brain in Freddie’s head was always buzzing and at war with itself. One could imagine Welsh constantly changing his mind and quickly tiring of trivial pursuits that failed to challenge his intellect. Freddie claimerd to be teetotal, a committed vegetarian and a non-smoker. And for most of the time, he was. He saw his body as a temple, long before such terminology became cool among the keep fit brigade. But this didn’t stop Welsh from partaking of the occasiomnal juicy chop, downing a nice glass of claret or puffing contentedly on those pleasantly lung-busting firworks known as Turkish cigarettes.

Always a crafty operator, the young Freddie got the idea to set himself up as an instant expert on physical fitness and culture, buying a book on the subject and making himself sound suitably worldly. Then one of the students in his regular class threw a spanner in the works by suggesting that speed balls were needed to hone hand and eye co-ordination. There’s always an awkward one.

Welsh, the great expert on such matters, had never punched a speed ball in his life. What he did next was typical of the way his mind worked. When the speed balls arrived, he bought himself time by dismissing them as sub-standard and demanding replacements. In the interim period he set about punching a speed ball assiduously in his own time until he had mastered the art.

For one whose introduction to boxing and its paraphernalia was accidental, it is generally agreed that Freddie Welsh did pretty well thereafter. But let us get back to the business and beauty of the left jab.

Thing of Beauty

Back in the early days of 1965, Mel Beers wrote a nice little article on Welsh for the sadly long defunt Boxing International magazine. Here is what Beers had to say about the most important punch in the boxer’s repertoire: “The left jab, properly used, is a thing of beauty in motion. It is boxing’s basic punch and those who mastered it usually went on to become world champions or leading contenders. Billy Conn and Willie Pep mastered the jab. So did Abe Attell, Packey McFarland and Benny Leonard. Tommy Loughran was another who built his boxing wizardry around a jab that shot straight and true to any part of the opponent’s anatomy.

“Who had the best left jab of all? It is impossible to say, but after plowing through piles of yellowed newspaper clippings and talking to scores of experts with long memories, the name of Freddie Welsh comes up more than any of the others.”

Now, add that great jab of Freddie’s to his athleticism, quick mind and natural cleverness, and you begin to see why he was so special. He was also a tough and rugged man into the bargain.

It is quite extraordinary how the simplest of weapons, when correctly employed, can not only endure throughnthe ages but completely negate and befuddle supposedly superior alternatives. Back in the mists of time, there was a fascinating little sparring match between an old and rusting Jem Mace and the brilliant Jem Driscoll. Such was Driscoll’s sublime skill that he made even Abe Attell look pedestrian in their classic New York encounter of 1909. Yet the few who were privileged to watch the session between Mace and Driscoll were astonished by Driscoll’s inability to keep Mace’s metronome of a left jab out of his face.

The rise of Freddie Welsh to the top of the tree was not meteoric or sensational. Like a surgeon perfecting his trade, Freddie picked his way through the ranks slowly, cautiously and often drearily. The chess-playing side of Welsh wasn’t always appreciated by impatient crowds who had paid their money to see some good old-fashioned violence. But Freddie kept winning and then learned his business in earnest when he travelled to America and began to beat the cream of the crop.

Boxing historian Mike Silver believes that Freddie Welsh is one of the most interesting characters to have ever won a boxing title. Here are Mike’s thoughts on the Welsh Wizard: “Welsh’s impressive performance against six of the greatest fighters of his generation says it all. During his prime he was a marvellous ring scientist whose mixture of orthodox and unorthodox moves puzzled and frustrated opponents for years. He possessed one of the keenest boxing minds in the history of the sport and was a true pioneer of his art.

“After losing a newspaper decision to a near prime Benny Leonard in 1916, Freddie figured out the chess moves for the return match and outpointed Leonard. News reports of that ‘no decision’ fight stated that Welsh had outboxed the future lightweight champion. How many fighters can make that claim? He did the same to Abe Attell and Johnny Dundee. The Welsh Wizard also held Packey McFarland to a 20-round draw.

“But perhaps Freddie’s most impressive performance of all was the time he made boxing master Jem Driscoll lose his cool. In their 1910 fight Driscoll was so frustrated by Welsh’s unorthodox methods and his ability to neutralise his great jab that Jem deliberately butted Welsh and was disqualified in the tenth round. It is obvious that even against great fighters, Welsh had the ability to make them fight his fight.”

Riotous

The fight with Driscoll was a riotous affair both in and out of the ring. Jem must have wondered how he ever contrived to lose the fight after the first five rounds in which his beautiful left jab ruled the roost. Freddie couldn’t get anywhere near the Peerless one.

But then Welsh finally got inside and hammered Jem with a series of hard kidney punches. Encouraged by not getting so much as a warning from referee ‘Peggy’ Bettinson, Freddie upped the ante as the fight rumbled on by roughing up Driscoll in the clinches with some artfully executed head butts to the chin. Still referee Bettinson would not issue a warning as the crowd hooted and jeered Welsh’s foul tactics.

From ringside, Jem’s reddened kidneys were clearly visible and it was clear to him that his complaints to Bettinson would continue to fall on deaf ears. For probably the only time in his professional career, Driscoll allowed his temper to fray. The red mist descended and all thoughts of science were discarded as he ripped into Welsh in a blind fury in the tenth round, pounding Freddie’s ribs with a succession of steaming hooks and swings.

The comical part of all this, as only true devotees would notice in such a bedlam, was that Jem never stopped punching correctly. Such was his God-given grace, he could swing ‘em in from the bleachers and still look a picture of technical perfection.

Then he gave Welsh some of his own medicine by butting him under the chin and throwing him across the ring. At long last, referee Bettinson woke up – and disqualified Driscoll!

What followed, and what continued for some time, was a gorgeous brawl between irate Irishmen and Welshmen throughout the hall, until a team of Cardiff police constables finally broke it up.

Mike Silver reminds us, quite correctly, that Welsh’s cagey and original style was a hybrid of both the English and American schools. Freddie took the classic elements of each and stirred them into his very own brew. “There was an unpredictable and deceptive quality to his work,” Mike notes. “An opponent never knew what he was going to do next. He could be a fine stand-up counter puncher and jab artist if it suited him, but he could also quickly morph into an aggressive in-fighter and mauler.

“His brilliant defence, the key to everything he did in the ring, kept him world champion even after he’d passed his prime. He utilised footwork – blocking, ducking, swaying and side-stepping to great effect. No one was able to stop him and take the title in a no-decision fight until Leonard figured out how to do it.”

Welsh’s great sense of timing and distance judgement were two other formidable assets that allowed him to maintain the ferocious schedule that was expected of the fighters of his era. Mike Silver reminds us of Freddie’s run-up to the world title, which required him to calculate his way through a minefield of golden talent: “After winning the newspaper nod over Johnny Dundee in January 1914, Welsh fought five more times that month! Four fights later, after having outpointed Joe Rivers and Leach Cross in 20-round bouts, he outfoxed Willie Ritchie for the lightweight title in yet another 20 rounder. That type of schedule would wreck today’s top fighters.”

Mountain

Freddie Welsh climbed to the top of the mountain when he dethroned Willie Ritchie and finally toppled off its peak against a Benny Leonard who was approaching his untouchable best. Both fights became etched in the memories of those who saw them.

Welsh’s disciplined mind was geared to expecting any opponent to be at his very best. He had heard of Willie Ritchie’s punching power and his big right hand. But Willie was a slow starter and he knew it himself as he prepared in his dressing room on the night of July 7, 1914, at Olympia in Kensington. He reportedly boxed the equivalent of six rounds with selected sparring partners as he awaited his call to the ring.

By contrast, Welsh, who might have made a good Mr Spock if he had come along later in life, was his usual precise self. A series of breathing exercises were followed by exactly 10 minutes’ sleep before he and Ritchie were notified that referee Eugene Corri had entered the ring.

Artful Freddie, who had injured his left eye in training, climbed through the ropes with a piece of sticking plaster over his right eye. The pattern of the battle was quickly set as Welsh employed his nimble footwork and quick hands to outbox the plodding Ritchie. For all his exertion in the dressing room, Willie just couldn’t seem to get out of the starting blocks.

With uncanny instinct, Freddie appeared able to anticipate Ritchie’s punches before Willie had even begun to twitch. On the rare occasions when Ritchie cornered Welsh, the skilful challenger demonstrated his all round ability by dropping the fancy stuff and fighting his way out.

But Ritchie’s reputation as a battler to be feared was not the stuff of myth. In the fourth round, he suddenly speeded up and became a more dangerous proposition, his streaking attacks making the contest a much more competitive affair. Welsh always retained the edge, but now it was a splendid duel of exciting out-fighting and intelligent close quarter work.

Watching the action was a good old writer of the time called Denzil Batchelor, who wrote: “There was no clinching. It was a beautiful fight to watch and as rare as it was beautiful. How many of the most eagerly anticipated fights of a lifetime consist, when we get down to statistics, of seventy per cent hugging and thirty per cent boxing? Referee Corri had told these two exceptionally intelligent boxers that at a tap on the shoulder from him they must break instantly. They obeyed him to the letter.”

While Ritchie’s famous right hand was always a threat to Welsh, Batchelor compared Freddie’s talent for blocking that punch with his left forearm as being almost the equal of Jack Johnson.

Only once, in a torrid tenth round, did Welsh get seriously caught. A peach of a right from Willie slammed against Freddie’s jaw and might have put him in serious jeopardy. But Welsh turned his head a vital fraction before the moment of impact, taking just enough steam out of the blow. Fighting back bravely but always intelligently, Freddie steered his way through the remainder of the battle to earn Corri’s decision and the world lightweight championship.

Freddie reigned for three years before Benny Leonard came calling again. Old gunfighters never stop being challenged and finally get beaten to the draw. Welsh had fought off opposition of mighty quality throughout his illustrious career, but even the engine rooms of the cleverest men eventually malfunction and wear down. In short, Freddie was in the autumn of his fighting years while brilliant Benny was just beginning to soar to those giddy heights that only the special few ever reach.

On May 28, 1917, in old New York, the 21-year old Leonard set a ferocious pace and made Welsh’s lean body the principal target. Punching hard and fast, Benny fired in accurate shots to the ribs and stomachs as he pursued the 31-year old champion constantly. Seeking to smash through the champion’s ring of confidence, the sprightly challenger cheekily stuck out his chin as an inviting target. Welsh was a boxer who rarely miscued tactically, but now he was being lured into errors by a similarly clever and agile mind. In the fourth round, Leonard nailed Freddie with that flashing right counter that would become a potent trademark of the brilliant New Yorker. Freddie’s head was thrown back and his knees dipped from the force of the blow. He couldn’t make his legs work for a few desperate seconds, but then he showed all his ring savvy as he bluffed and hustled his way through the crisis.

In truth, however, the old stager was just delaying the inevitable, as great and proud champions do. He must have known it was over, just as the equally instinctive Leonard must have realised that this was his big night. He was on Freddie in a flash at the start of the ninth, knocking the Welshman down with a right that cut straight through his defence. Stubborn pride got the better of Welsh, who jumped up without taking a count and walked straight into a firestorm.

Leonard swept straight through Freddie’s brave defiance, cutting him down for the second time with another cracking right. It was a blow that sent Freddie’s mind into an inescapable fog. He was an easy target when he got to his feet and the final driving blow from Benny – a left this time – left the broken champion in an eerie limbo. Somehow he remained upright, but he was gone as he grabbed the ropes and staggered drunkenly against them. Leonard moved in to apply the coup de grace, but the referee intervened and stopped the fight just as it seemed that Welsh would tumble through the ropes.

There would be other fights for Freddie. The temptation to come back is always a powerful drug for a fighter to get out of his system. He returned to action in 1920 but enjoyed only moderate success before retiring in 1922. The end? Oh no, not for someone like Welsh. He never did lose his love of physical fitness (including that odd glass of claret and Turkish cigarette) and enjoyed a nice old time as the boss of a health farm for millionaires in America.

As Denzil Batchelor concluded: “God bless my soul, sir, there was only one Freddie Welsh in the world.”

Mike Casey is a freelance journalist, boxing historian and a member of the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO). He is also a well known modern and abstract artist whose works can be viewed and purchased at www.artgallery.co.uk/artist/mike_casey