06.02.09 – By Mike Casey – For once, let us not major on the quartet of fights against the mighty Sugar Ray Robinson. Those battles are etched in the memory of fight fans and film collectors and they haunted Carl (Bobo) Olson for long enough. That is not to say that we can conveniently erase those losses in examining Carl’s greatly impressive record. We cannot cheat by doing that, any more than we can make the niggling name of Muhammad Ali vanish from the records of Sonny Liston and George Foreman. Yes, I know, Sonny and George would have reigned for ever if they hadn’t made a hash of it against old Big Mouth. But they did and we can’t wipe that evidence from the slate in court.

06.02.09 – By Mike Casey – For once, let us not major on the quartet of fights against the mighty Sugar Ray Robinson. Those battles are etched in the memory of fight fans and film collectors and they haunted Carl (Bobo) Olson for long enough. That is not to say that we can conveniently erase those losses in examining Carl’s greatly impressive record. We cannot cheat by doing that, any more than we can make the niggling name of Muhammad Ali vanish from the records of Sonny Liston and George Foreman. Yes, I know, Sonny and George would have reigned for ever if they hadn’t made a hash of it against old Big Mouth. But they did and we can’t wipe that evidence from the slate in court.

This is no ‘what if’ article on Carl Olson, because we know for a fact that his stock in the all-time stakes would be considerably enhanced if, at the very least, he had split those four fights with Robbie. We will assess the Robinson factor a little further on.. The principal objective here is to remind ourselves just how good Olson was in a fearsomely competitive era, since his many achievements are often overlooked. Bobo was a typically tough man of his era, but certainly not the toughest. He wasn’t a classic boxer or a natural born puncher. His harrying style was an odd mixture of aggression and determination, which would invariably keep his opponents too busy to expose his weaknesses. One writer aptly described Olson as “…. a tireless ringman with a persistent, slashing attack.”

First and foremost, perhaps, Carlo (Bobo) Olson was a passionate fighter, a hard and thoroughly schooled battler like so many of his great contemporaries in the late forties and fabulous fifties. For that was the slow fading era that proved to be the glorious autumn of boxing’s so-called Golden Age. Olson showed no fear when he went into battle. All business and urgency, he resembled an impatient terrier trying to break free from its leash. He jabbed, hooked, hustled and bustled, jinked and ducked, yet never in such a definitive way that made his style easy to categorise. He was a dominant world middleweight champion who was frequently drained at the weight after last minute jogs and steam baths. He beat top ranking light heavyweights and even had the occasional bash at the dreadnoughts. He fought the best and only lost to the best in 115 professional fights.

We tend to forget just how good Carl was at his very best. He was three to one over Archie Moore when he challenged Archie for the 175lb crown in 1955. As fanciful as it may sound now, Olson was being seen as a viable challenger for Rocky Marciano’s heavyweight championship. Bobo was bobbing along and enjoying a fantastic run at that time. Approaching the peak of his powers, he began his great winning streak with a commanding victory over Randy Turpin for the vacant middleweight championship at Madison Square Garden on October 21, 1953.

Succession

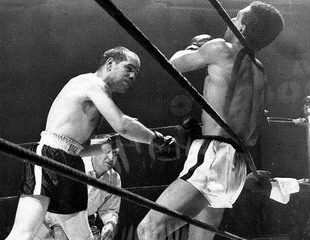

Olson was all over former champion Turpin that night, launching a succession of wave-like attacks throughout the 15 rounds that must have seemed interminable to the beleaguered Englishman. The capacity crowd of 18.869 roared in anticipation whenever Bobo surged forward and trapped Turpin on the ropes. Yet the start of the battle gave little clue as to what was to follow. The eager Turpin came out fast in his familiar and almost uniquely upright stance, pestering and puzzling Olson with a persistent, stinging left jab. Carl grabbed whenever he could, the only way that he could avoid the tormenting blow. Heavy at 157lbs to Olson’s 159½, Randy seemed to be trying to get the business done quickly and continued his busy attack through the second and third rounds.

But two things were noticed by those at ringside in the third session. Olson was gradually gaining a foothold and Turpin, worryingly, was gulping for air. In the fourth round, Bobo began to roll in earnest and the scales tipped dramatically in his favour. A meaty hook to the body had Randy hanging on, and the first drops of blood from a wound to his left cheekbone began to fall.

Turpin’s successes thereafter were few and far between. He rattled Carl with long rights to the chin in the eighth and eleventh rounds, but Olson just wouldn’t give his opponent sufficient room to conjure a turn of the tide. Chugging forward and punching away, Carl shut Randy down with repeated volleys that confined the harried European champion to a largely defence-only mode. The telling rounds were the ninth and tenth, when Olson made a significant breakthrough. He floored Turpin at the end of the ninth stanza and then Randy looked in dire straits in the tenth when Olson pummelled him to the canvas for a count of nine. Blood flowed from Turpin’s cut cheek and he was left with a mountain to climb. The decision was unanimous for Bobo, with only judge Arthur Susskind seeing the fight as a close affair with a tally of 8-7. Judge Charley Shortell had Olson winning by 11 to 4, while referee Al Berl tabbed it 9-4-2. The Associated Press saw the battle as a 10-4-1 triumph for Olson.

Hawaiian Swede

Carl (Bobo) Olson came from mixed stock. His mother was Portugese, his father Swedish, and the family ended up in Honolulu when Carl’s father was stationed there with the armed forces. Bobo, who was born in the summer of 1928, became known as the Hawaiian Swede during his boxing career, and he started scrapping early in life like most kids who have it in the blood. He fought in the streets, in the local gym and in bootleg fights at the army camps. Olson learned fast and always came back for more after a beating. In the camps he was going up against experienced fighters, many of them professionals, and more than holding his own. The hook was in and Carl turned professional at the age of 16, making his debut in Honolulu in the summer of 1944. With that usual brand of ingenuity that comes naturally to fighters, he had undercut the required age limit by five years thanks to a false identification card and a couple of hastily arranged manly tattoos on his arms.

In the days when a fighter either stayed busy or got forgotten, Olson zipped through the ranks at a fair old lick as he racked up 40 fights in five-and-a-half years and dropped just two decisions. He was beating tough cookies like Tommy Yarosz, Anton Raadik and Milo Savage and edging closer to the top boys of the division. The third reverse of Olson’s career came in 1950 and was certainly no disgrace. At the Sydney Stadium in Australia, he was outscored by that gifted ace, Dave Sands, whose untimely passing a couple of years later would leave the boxing world wondering how great he might have become. Sands, incidentally, had notched 110 fights by the time of his death at the age of just 26.

Undeterred by the loss, Bobo was back in action in his native Honolulu just a month later and recorded three straight victories before meeting the great Robinson for the first time. The two men clashed for the Pennsylvania State version of the middleweight championship at the Convention Hall in Philadelphia in October, 1950. Nowadays, most of the highlight reels on Robinson’s career show only his last two fights with Olson, when Carl was knocked out in two and four rounds respectively by sudden thunderclaps that seemed to come from the gods. Those spectacular finishes often obscure the fact that Bobo gave Ray some serious and intense competition in their first two encounters. Olson gave a fine account of himself for eleven rounds in the Philadelphia match, until manager Sid Flaherty reminded him that Robbie would come on like a train in the later sessions. It was the kind of well meaning advice that either encourages a fighter or plants a destructive seed in his mind. Carl suddenly became more conscious of what he was doing and a little more cautious as a result. Ray seemed to smell the uncertainty and gunned Bobo down in the twelfth.

How did Olson react to that? Why, he kept on rolling of course. He countered a second points defeat to Dave Sands with seven victories before having a second crack at Robbie in San Francisco in 1952. Now Robinson was the undisputed champion, still royally magnificent but no longer untouchable after his two adventures with Randy Turpin. Bobo gave it everything as he followed a smart and somewhat impudent game plan. Mimicking Robinson as best he could, Carl set about replying in kind to everything Ray threw and then some. Robbie’s combination punching had perplexed Olson in their first fight and ultimately proved his undoing, so Bobo fired off volleys of his own in the rematch, keeping the great man constantly occupied and banking his fire. It was some plan too. Carl lost the decision, but the fight was a very close affair in the eyes of many.

Years later, Olson told writer Pete Heller, “In my mind, Robinson was pound for pound the greatest fighter that ever lived. To know that I came real close like that when he was knocking out guys like Rocky Graziano and LaMotta, I was glad just to go the whole 15 rounds and come so close. I had the confidence after that.”

He did too. His admirable record proves it. But did he ever really have the confidence to beat Robinson? He surely gives us the answer to that question in those few telling sentences. Nevertheless, in the following three years Olson would prove all-conquering against the best men around. Robbie cleared the path with his early retirement and Olson became the top dog with a succession of sparkling victories. After vanquishing Turpin for the vacant title, Carl entered his golden year of 1954. His first challenger was welterweight champion, Kid Gavilan, who slapped on too much extra poundage for his own good and lost vital speed as a consequence. Olson was much stronger and more vibrant throughout the 15 rounds, firing off punches all the time and keeping constant pressure on The Keed. Carl had all but perfected his crowding, hustling style, where the objective was to cramp the other man’s space, cut off his options to manoeuvre and not allow him sufficient time to fashion a solution. Only on one occasion was Gavilan, normally such an exciting and free-flowing spirit, able to bring his famous bolo punch out of mothballs and tag Olson significantly.

Carl proved emphatically in this fight that he possessed the good champion’s gift of being able to assess his opponent’s style and gridlock it. He was more or less Gavilan’s equal in jabbing and certainly the master in short range punching. Olson also proved adept at avoiding blows by deflecting them with his elbows or cleverly stepping to one side. Ring editor Nat Fleischer was greatly impressed when he concluded, “So ended Gavilan’s dream to win the middleweight crown and take his place with Ray Robinson as holder of the welter and middleweight championships at one time. He learned, as has so often been recorded, that good welterweights do not defeat good middleweights who possess stamina, power, courage and the other assets that go with an excellent fighting machine. Such a fighter is Carl (Bobo) Olson.”

Tightrope

It is surely further testament to Olson’s ability and determination that his success as a middleweight came in spite of the tightrope he consistently walked in draining his weight to the required 160lb limit. It became a constant saga. Before he trimmed his opponents, Bobo had to trim the pounds. He was a pound over the limit for his next challenger, Rocky Castellani, and had to work out for an hour to shed the offending surplus. Once again Olson pulled off the delicate balancing act, outclassing Rocky over 15 rounds at the grand old Cow Palace in San Francisco.

Castellani was a top contender and a tough man, a typical example of the hardened men of his era. Rocky won 65 of his 83 fights in a 13-year career that began in 1944. Who did he fight? Now there is a question that prompts a veritable cannonball to come thundering back in our direction. Try this little list for size and then cross reference the glittering names: Harold Green, Walter Cartier, Charley Fusari, the clever Tony Janiro, Kid Gavilan, Ernie Durando, Gene Hairston, Joey Giardello, Ralph (Tiger) Jones, Johnny Bratton, Billy Graham, Pierre Langlois, Gil Turner, Holly Mims, Gene Fullmer, Ray Robinson, Joey Giambra, Bobby Boyd, Rory Calhoun.

Against the fiery Olson, however, it was felt by many that Castellani squandered a golden chance of glory by fighting negatively and showing the champion too much respect. Rocky discovered early that his right hand could not only tag Bobo but hurt him. Yet the immensity of the occasion seemed to keep Rocky in handcuffs as he too often clutched and retreated. When he finally shed his inhibitions and decked Bobo for a brief count in the eleventh round, Castellani failed to follow up on his advantage. The knockdown angered Olson, who claimed he had been struck on the shoulder by a blow that was more of a shove. The champion tore from his corner in the twelfth and let loose a big right of his own that knocked Rocky down for a nine count. The challenger was hurt and glassy eyed but survived the crisis to last the full route and lose a wide decision.

It seemed there was no stopping Bobo Olson and that there were no boundaries to his domain. The formidable likes of Archie Moore and Rocky Marciano were becoming realistic targets. Over the next eight months, Olson saw off Pierre Langlois in another successful title defence and surrounded that triumph with quality victories over Garth Panter, Ralph (Tiger) Jones and Willie Vaughn. But the gates of opportunity really opened when Carl outpointed former light heavyweight champion Joey Maxim in San Francisco in April 1955, decking tough Joey twice in the process. Archie Moore was up next. And Olson was a big favourite to beat the old man.

Quality Street

A fighter can only improve and realise his true potential if he is fighting frequently against quality opponents of all levels who can teach him to expand and hone his technical repertoire and enhance his mental toughness. Sadly, that isn’t always possible now, as the field of competition in all weight classes is too barren and too lacking in depth of talent. How else is it that a man can now challenge for a ‘world’ title after 10 or 12 fights? These men aren’t whizz kids or geniuses. Many of them disappear off the radar completely after that brief moment of glory in which a cheap and tacky belt is slapped around their waists for winning a paltry portion of something that was once revered.

In Bobo Olson’s time, the pickings were rich and the professors were plentiful. Top contenders, be they boxers or sluggers, were seasoned men of great boxing knowledge. Even the so-called ‘journeymen’, many of whom would be world champions today, could teach a rising prospect every trick in the book and give him a sore beating into the bargain if he didn’t have his wits about him.

Dan Cuoco, director of the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO) has some strong and pertinent feelings on this subject. When my fellow historian, Mike Silver, was compiling his excellent book, The Arc of Boxing, Dan offered Mike the following thoughts: “It’s like playing tennis with someone that’s not as good as you are. You’re not going to improve. But playing with somebody that’s as good as you are will improve your game, and if you start playing with opponents that are even better, you’re going to become a better player yourself. And that’s the same thing in boxing.

“Let’s say you were to evaluate at random any of the top middleweights from the 1950s – for example Bobo Olson and Joey Giambra – and made a list of their opponents and then gave the opponents a grade based on overall skill level and the type of opposition they faced. Then do the same with Bernard Hopkins, a modern day champion who many people think is an all time great fighter. I think the outcome would be a no brainer. The old timers’ level of opposition is going to win out every time. When you take a look at who Giambra and Olson fought – guys like Tiger Jones, Joey Giardello, Dave Sands, Billy Graham, Ernie Durando, Spider Webb – you can see the difference in the caliber of opposition.”

Bomb

The bomb that was dropped on June 6 1955 at the old Polo Grounds in New York was delivered with all the craftiness and cunning that one had come to expect of Archie Moore. It came in the form of a sudden, booming left hook that left Carl (Bobo) Olson in a state of paralysis on the canvas in round three. Bobo’s carefully cultivated points lead had been eaten into and then gobbled up by a succession of skilfully placed body punches that paved the way for the spectacular coup de grace. The effects of the blow took a while to work their way through Olson’s body. Helped back to his corner, he crumpled again from the after shock. There was no more talk of a fight with Rocky Marciano.

Archie Moore picked up close to $90,000 for that fight, his first purse of any great significance after years of campaigning. Olson would later claim that he didn’t pick up a cent due to the questionable ‘investment’ policy of his manager, Sid Flaherty. A cosy layoff, where Bobo could rest his bones and ponder his future, was therefore out of the question. Within two months of crawling from the wreckage of the Moore defeat, Olson was winning a decision from Jimmy Martinez. Two weeks after that, Bobo was posting a unanimous victory over one of the finest middleweights of the era in the artful Joey Giambra. You didn’t go fighting Joey if you were feeling a little fragile and sorry for yourself.

Then Sugar Ray Robinson, disillusioned at trying to get by as an entertainer, decided to come back and regain the middleweight championship of the world – as one does. After a temporary blip against Ralph (Tiger) Jones, who never gave a tinker’s cuss for anyone’s reputation, Ray peeled off four straight wins before challenging Bobo for his title at the Chicago Stadium in December 1955. The exertion of making the middleweight limit was now taking its toll on Olson’s body. Right from a young man, his natural weight had been close to 190lbs. There was certainly a ghostly and faded look to him in his last two fights with Robinson, but then there was also the gut feeling that Carl would never have beaten Ray in any circumstances. Fate, one feels, had simply decreed it.

Robbie, as ever, was perfectly poised and balanced at the Chicago Stadium, a worldly gunslinger waiting for the right moment. He opened the fateful second round by jabbing well and scoring with a right. He always tossed in that right cross with such speed. Olson was having trouble finding any consistent success as he winged at Ray with lefts and rights and tried the occasional uppercut. Then the boom was lowered with shocking suddenness, as it so often was with Robinson. Two whiplash left hooks sent Bobo to the canvas, scattering his senses and incapacitating his legs. He couldn’t beat the count.

Five months of welcome rest followed for Olson before his concluding chapter with Ray at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles in May 1956. Alas, the elapse of time didn’t shake up the planets and stars and change the natural order. It simply granted Bobo an additional two rounds before Robinson released the guillotine once more with similarly cold precision. A right to the ribs and then a peach of a left hook to the jaw in the fourth round sent Olson down and out. That left hook, and its sister bomb that would wreck Gene Fullmer a year later, remain two of the purest knockout blows this writer has ever seen.

No Man’s Land

For the first time in his career, Bobo seemed to be losing his way and becoming the forgotten man. The fierce competition of the boxing ring in those days was reflected in the unforgiving and fickle nature of its media. If you weren’t winning, you quickly plummeted down the rankings and out of the spotlight. There were too many other fighters to write about to indulge in sentimental articles on how a former champ was making out. It is here that we have to admire Carl Olson’s incredible resilience. For he was digging himself out of no man’s land when he dusted himself down to forge a second career as a ranking light heavyweight. He was never among the most durable or rugged of fighters, but he was a rock of a man in spirit. He needed to be, since his battles weren’t confined to the ring.

As times changed and journalists were permitted to hit harder, so the details of Bobo’s complex private life became more juicily discussed. There was plenty of material there for the mischievous, including Olson’s bouts of heavy drinking and the fact that he was supporting two wives and eight children before his first missus tumbled the plot. Perversely, one couldn’t help but admire Bobo for his ability to compartmentalise his complicated life and keep his head above water.

Like a stubborn mule, he simply refused to be shunted into retirement during that last phase of his career, even though his notable successes were countered by dispiriting defeats. Nor was he content to pad his record against opponents who could do him no harm. Bobo continued to fight and beat the best of his class, impudently forcing his way into the light heavyweight top ten. He notched victories over Mike Holt, Sixto Rodriguez, Sonny Ray, Jesse Bowdry, Wayne Thornton and Andy Kendall, and fought draws with Guilio Rinaldi and the highly capable Hank Casey. On his thirty-eighth birthday in 1966, Olson cheekily took a decision off European champion, Piero Del Papa.

But the defeats were painful reverses. Bobo was knocked out by Doug Jones and Jose Torres and dropped a decision to the rising Johnny Persol. The final curtain came down after a points loss to Don Fullmer at the Oakland Arena in November 1966.

The Torres disaster, in one electrifying round at Madison Square Garden, hurt Bobo the most, for he had been so confident of victory. A title fight with Willie Pastrano would have been the prize. Olson was clearly distressed in his dressing room. “This had to happen,” he said, “just when I can’t stand something like this to happen.”

At Toots Shor’s restaurant that night, Bobo declined steak and champagne and ordered the modest fare of a plate of hash with an egg on top. It was an honest and oddly classy little concession.

Mike Casey is a boxing journalist and historian. He is a member of the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO), an auxiliary member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and founder and editor of the Grand Slam Premium Boxing Service for historians and fans (www.grandslampage.net).