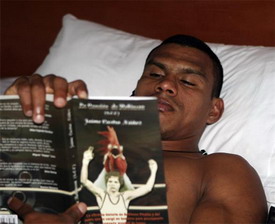

By Luis Orlando Ramírez, Ph.D. – While IBF Light Welterweight champion Juan Urango read two months ago “La Canción de Robinson,” [Robinson’s Song] by EastSideBoxing contributor Jaime Castro-Núñez, I only had the opportunity to read it over the Easter weekend. Now, if there is a reading battle between the IBF champion and the PhD professor, I must confess “Iron Twins” threw another of his vicious left hooks directly to my chin. Who said boxers don’t like to read?

By Luis Orlando Ramírez, Ph.D. – While IBF Light Welterweight champion Juan Urango read two months ago “La Canción de Robinson,” [Robinson’s Song] by EastSideBoxing contributor Jaime Castro-Núñez, I only had the opportunity to read it over the Easter weekend. Now, if there is a reading battle between the IBF champion and the PhD professor, I must confess “Iron Twins” threw another of his vicious left hooks directly to my chin. Who said boxers don’t like to read?

With that being said, let’s talk about Castro’s new book. Written in the Spanish language, the 353-page book tells the inspiring (and sad) story of Colombian featherweight boxer Robinson Pitalúa, who positively impressed boxing experts during the 1984 Olympic Games held in Los Angeles. Pitalúa turned pro after the Olympics and a year later promoter Felix “Tuto” Zabala relocated him to Miami, where he drowned while swimming with a friend on September 22, 1985.. He was only 21 and his professional record was 6-0-0, 4 KO’s. During the early 80´s Robinson Pitalúa was considered Colombia’s greatest prospect, according to The Ring.

I started to read the book on Friday morning and stopped a couple of hours later on page 142. I resumed the task the same day around 11:00 PM to finish it off eight hours later in what became one of the most exciting reading journeys I ever had. The fifth chapter, whose English translation would be something like: “Knocked Out by the Sad Moments,” has such a tremendous emotional load that actually made me cry. That’s the part where the author describes the tragedy, the desperate search of the body, the uncertainty that embraced his promoters in Miami and his relatives down in Colombia, the painful scene that took place on Monday, September 23 at 10:45 AM, when police divers pulled the body from the bottom of the West Dade lake, the shipping of the corpse for burial, and how people, family and girlfriend dealt with his early departure. The following is a translation:

“Three years later [After Pitalúa’s burial], on September 23, 1988, the family exhumed the corpse. They did everything silently, in private. All of them were at the cemetery: parents, brothers, sisters, nephews, nieces, in-laws and relatives wearing mourning clothes and bouquets of white flowers. The gravedigger began to destroy the cover of the vault. He hit it for the first time, bang, once again, bang, then three more times, bang, bang, bang, until he destroyed it. Nobody else was in the cemetery and the birds sang on the highest branches of the mango trees. They pulled the casket and, contrary to what they had thought, it was cold, very cold, because the cooling system with which it had come from Miami was still running. They opened the casket and “there was my beloved son, intact.” The crucifix was preserved, but the boxing gloves did not resist the humidity.

The day in which the corpse arrived to Montería the family could not see him because the multitude willing to say good-bye to the champ did not let them. But there, in the solitude of the Garden of Hopes Cemetery, they had the chance to see him. They stood in silence, contemplating Robinson because he still kept the factions. Embraced like in the best times of romance, María Elena and Rafael approached the coffin. They recalled the day in which he arrived in the world at the small house of La Gallera neighborhood, so awake, so agile, so playful. They hugged each other and cried out again like they did the rainy morning in which RCN radio station confirmed his son had drowned. Mr. Rafael pulled a white, scented handkerchief from the left pocket of his pants in order to wipe off his wife’s tears. He did so delicately, absolutely caught by the heart of that slim brunette woman in whose entrails he had planted ten children. “I love you” –he told her with cracked voice.

Amparo Acosta Morales approached the remains. She had saved the photo album during the last three years to show it to him when he come back, “look my dear, people said you were dead and they even brought in the news, although I knew you were alive,” but when she stood in front of him she finally realized his boyfriend was asleep. She took off the dark glasses and a tear fell on the champion’s chest. She recalled the words he said before the last fight, so expressive, so happy and so full of life: “Not much, honey. Here I’m with this long hair that upsets me.” She saw him with a nice haircut, shiny, wet. Then she reconciled the bones under her eyes with the easygoing boy who was still living inside her heart. “Yes, that’s him,” she said to herself pressing the lips and looking down to the floor full of dry leaves.

She remembered the tree where they had carved their names. She had impatiently awaited for his return to redo the names, “I hope he comes back soon because our names are disappearing”, but when she was aware of the fact that Robinson would never return, she carved their names in her heart so the scar will remind her twenty-four hours a day, the seven days of the week, that for her life had passed by a boy named Robinson whose memory would not be defeated by time, aging or even death. She took a deep breath, wiped the tears off, wore again the dark glasses and went to the corner so that others might see him, now for the very last time.

Eighteen years later, in 2006, the family met at home to remember another anniversary of the tragedy. Since 1986, every year by the same date, journalists, writers, historians, sports leaders, students and friends go to Montería’s 41st Street to celebrate the inspiring life of the champ. They do so because Montería cannot forget Robinson Javier Pitalúa Támara. They do it because Robinson has become the first Montería-born who beat death. He came, stayed, marched, fought, and walked a way leaving behind him an example of life. He was among us only twenty-one years, but they were enough for him to light a torch that burns today more than yesterday.

But that September 2006, was very special. His sister María del Rosario realized how quickly time had passed. “Shit, twenty-one years already!” She expressed that with firm voice, owner of her words, in a manner she never ever thought she would be able to say them. She realized that time had healed the unfathomable wound and that Robinson’s belongings were mislaid. She looked for his passport, but could not find it. She thought of his wallet and began to dig into the drawer where Dad had kept it for so long that perhaps it no longer was in the same place.

Two decades ago everything was so fresh as to put her nose on his brother’s wallet, but after all these years, how important would it be? María del Rosario opened it with solemnity, as if she had on her hands the Act of Independence signed on July 20, 1810 by the Colombians seeking independence from Spain. One by one, she removed all the documents he had on it. She saw the same piece of green paper Mr. Rafael saw when promoter Tuto Zabala gave him the wallet. She read: “Tuto Enterprises, Inc. Dec. 28, 1985. Pay to the order of Rafael Pitalúa, two thousand dollars.” It was a check that Zabala put inside the wallet. Zabala did not have to do that, but at the time he deemed it necessary, perhaps as a consolation prize. But since nobody ever searched the wallet, the check slept in the same place throughout the years.

Maria del Rosario sighed. She closed her eyes for a second in order to revive the family’s greatest moments along with Robinson and saw them very happy during the Olympic Games, so cheerful when he returned victorious from Neiva and so full of hope on the night of the professional debut, that she got hurt when returned to the present. It was just a second in which everybody returned to youth and saw Dad solid, strong and without gray hair; mom so beautiful with her skin smooth and unwrinkled; her brothers lifting weight to conquer ladies and her sisters in front of the mirror retouching their lips for Saturday’s party. She recognized the champion’s belt on top of the anatomy books, the diploma, the stethoscope and the scalpel. Then she saw herself inside the emergency room while the doctor ordered: “Push harder sister, push harder.” She felt happy, absolutely amazed by all the things that happened and also by those that could be and never were. She opened the eyes and looked again at the check she had on her hands. “My poor brother!” –she said while a tear fell down her cheeks.

The clever aspect of this book, in my opinion, is that the author goes beyond the tragedy and, using simple words, narrates the story so vividly that Robinson Pitalúa comes back to life to fulfill his dreams of becoming champion of the world and a well-respected medical doctor. It means that sometimes writers get handcuffed by the unfulfilled dreams of the boxers. It means that sometimes writers get jailed into the ring. La Canción de Robinson by Jaime Castro-Núñez is published by Nomos Press, Bogotá, Colombia, and it is distributed in the USA by Mrs. Lyda Amaya at (310) 473-3098 and/or lydajota@hotmail.com

***

Professor Luis Orlando Ramírez teaches history and currently works on a biography of former world champion Nicolino Locche.