17.07.08 – By Mike Casey: Some time back, when the secretive lair was finally penetrated and the crown jewels sparkled in the sudden sunlight, I realised with a sense of wonder that every great thing ever said about Nicolino Locche was true. There he was, moving casually and almost contemptuously around the ring, an imperious master of his trade, taunting his hapless opponent with gifts of body and mind that only come from the gods. The hapless opponent was Antonio Cervantes, who was only one of the greatest junior welterweights that ever lived. What does that tell us about Locche? It tells us volumes. He pitched a 15-0 shutout on the cards of all three judges in that unforgettable exhibition of pure boxing. Yes, the fight was in his native Argentina. No, it wasn’t hometown favouritism gone mad.

17.07.08 – By Mike Casey: Some time back, when the secretive lair was finally penetrated and the crown jewels sparkled in the sudden sunlight, I realised with a sense of wonder that every great thing ever said about Nicolino Locche was true. There he was, moving casually and almost contemptuously around the ring, an imperious master of his trade, taunting his hapless opponent with gifts of body and mind that only come from the gods. The hapless opponent was Antonio Cervantes, who was only one of the greatest junior welterweights that ever lived. What does that tell us about Locche? It tells us volumes. He pitched a 15-0 shutout on the cards of all three judges in that unforgettable exhibition of pure boxing. Yes, the fight was in his native Argentina. No, it wasn’t hometown favouritism gone mad.

What was it about Argentina and other exotic lands when I was growing up in the sixties? They seemed to be cloaked in as much secrecy as the Soviet Union and China. Nothing seemed to get smuggled out. A glimpse of Locche or Eder Jofre on moving film was a rare treat.. The truth, I suspect, was plain old-fashioned laziness on the part of the staid and parochial American boxing media of that time. Who ever profiled Nicolino Locche in any great depth? How many writers from the established titles of the day knew he was even there? A genuine fistic genius was our midst, plying his trade with all the finesse of a master painter, but the poor fellow came from Argentina and how the hell did you pronounce that surname? The old men of the Ring magazine were far too busy lambasting Muhammad Ali and Sonny Liston and telling us that only a few fighters who came along after Jack Johnson were worth a damn. If you never leave New York, you’ll never know what’s going on in Beunos Aires. Nat Fleischer went on his periodical world jaunts and credited the likes of Jofre, Pascual Perez and Pone Kingpetch for being special talents. But for the most part, boxing in the Americas and the Far East was compressed into small print to fill the back of the magazine.

While Mr Fleischer and his weary, near-octogenarian troops (and fellow historians will know that I have praised those gentlemen quite often in many other regards) were bemoaning the dramatic drop in live boxing audiences, the likes of Locche, Perez, Jofre, Carlos Ortiz and Flash Elorde were filling giant soccer stadiums in those odd countries where they spoke in strange tongues. Massive crowds would stomp and cheer and sing in joyous praise of their gladiatorial heroes. The Argentinian fans would often sweep Locche home on a wave of celebratory song, safe in the knowledge that the ever shifting, liquid-like armour of their idol could not be pierced.

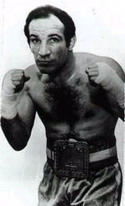

Locche was a physical contradiction and I think that is why so many boxing fans are stunned when they see him in action for the first time. In and out of the ring, Nicolino was no obvious athlete. Like his compatriot and fellow legend, Carlos Monzon, Locche was a heavy smoker all his life, yet his ability to store and conserve his energy in combat was frequently lauded as exceptional. Monzon was a similar freak of nature, known as ‘Iron Lungs’ to those around him. Manager Amilcar Brusa once said that he never saw Monzon gulping for air in a fight. It was quite common for Locche to take a few drags on a cigarette between rounds while his seconds did their best to conceal the act.

Balding, barrel-chested and thick shouldered, Nicolino resembled a slugger or the kind of beefy trialhorse who rarely wins but can give or take all night long. Tough and brawny boxers of remarkable durability have long been produced by the score in Argentina. There are countless, barely known journeymen with patchy records who can box sublimely, slug with the best of them and go the distance every time. The vast majority of these men, save for the odd bad apples found in every barrel, are wonderfully schooled and hard as nails. In his appearance alone, Nicolino Locche would have been completely lost in their midst.

Once in motion, however, he blew all stereotype images from the mind. His was a lazy, languid, impudent style that was all his own. He was genuinely unique among the great magicians of the ring and I haven’t seen his like since. He was a grand master of all the essential technical skills and invented his own little eclectic collection into the bargain. He was ‘El Intocable’, the untouchable. What he didn’t possess was a knockout wallop, and how convenient that was for certain lazy writers whose ‘research’ on Locche was to simply glance at his long record and highlight the 14 knockout wins from the staggering total of 117 triumphs, 14 draws and just four losses in 135 battles.

I’m sure Nicolino didn’t lose too much sleep over the lack of powder in his cannon. Who cares about a knockout punch when you can clean a skilful and destructive hitter like Antonio Cervantes by a score of fifteen to zero?

Locche could blind an opponent with science in every way imaginable. His box of tricks was bottomless. He would bend forward from the waist, sometimes locking his gloves behind his back, stick his chin up in the air and cheekily invite uppercuts and slashing punches of despair that never struck him. The meaty, protruding head would twitch one way and then the other as the incoming missiles passed by and worked up a cool breeze.

Locche was rarely a ‘runner’ in the ring. The thought of running, or for that matter any exercise of great exertion, would likely have horrified him. Such was his confidence in his breathtaking ability, he would often position himself squarely in the line of fire and trust his physical and mental instincts. Like a cuddly bear on castors, he would slide forward, jig sideways or move back with a casual yet oddly comical grace. Sometimes he would look like an old man with a bad back as he stepped and shuffled in and out of his appointed circle, before suddenly shooting out a jab or winging a hook to the body with lightning athleticism. He could box at range or box in close, fight off the ropes or rush an opponent without looking at all awkward.

How sickening his talent must have been to a generation of quality men who were made to look uncharacteristically clumsy as they slashed and swiped at the air around him. For a seasoned ring mechanic who has learned his trade and done it all, there is no worse feeling than that of inadequacy. Locche teased and taunted and smiled, and even conducted running conversations with people at ringside. When Muhammad Ali subsequently did likewise, he was hailed as a roguish one-of-a-kind. But while Ali was flamboyant and flashy, Locche was deft and dexterous, infinitely cleverer and more knowledgeable. While Ali was intense and passionate, Locche was calm and casual and saw no point in inflating the compact economy of his blindingly apparent genius. Boxing to him, it seemed, was as pleasant a way as any to pass the time between cigarette breaks and other less rigorous pleasures.

Record

In examining Nicolino Locche’s sprawling record, it is important to understand the nature of Argentinian boxing. You will see a lot of draws on the early records of many great fighters. They are well protected when they are learning and developing, and close fights between young prospects are invariably deemed stalemates. I don’t doubt for a moment that Locche was done a few favours on the way up, just as the young and raw Carlos Monzon may have similarly profited from the kindness of judges. But neither of these wonder boys needed crutches to stand up. Their records glitter with first class quality and achievement.

A while back, writer Martin Sosa Cameron compiled a nice little biography of Locche for the CBZ, in which the maestro’s many accomplishments were neatly encapsulated. Here is the gist of what Martin wrote: “From 1958 to 1964, Locche made 55 bouts without a loss (winning 45 and drawing 10), and between 1964 and 1972, when he lost his title to Alfonso (Peppermint) Frazer, he was unbeaten in 57 fights (won 54 and drew three). Through 1973 to 1976, he won his last seven fights. He faced the best men of his weight in their primes. Among his most important wins are Joe Brown (1963), Sandro Lopopolo (1966), Eddie Perkins (1967), Paul Fujii (1968), Carlos Hernandez (1969), Antonio Cervantes (1971) and Pedro Adigue (1973).

“Locche also drew with Ismael Laguna (1965) and Carlos Ortiz (1966), all world champions. Laguna, Ortiz and Lopopolo were holders of the belt in non-title bouts, and against Fujii, Locche obtained the junior welterweight championship. He also scored notable victories over Jaime Gine, Vicente Derado, Eulogio Caballero, Manual Alvarez, Tony Padron, Sebastian Nascimento, Raul Villalba, Roberto Palevecino, Abel Laudonio, Hugo Rambaldi, Everaldo Costa Azevedo, L.C. Morgan (who previously beat Jose Napoles), Abel Cachazu, Al Urbina, Juan Salinas, Juan Aranda, Joao Henrique, Adolph Pruitt, Benny Huertas and Jimmy Heair.”

The Quick And The Clever

Locche was ample proof that ring cleverness comes in all kinds of packages, so perhaps this is an opportune time to establish the strict parameters in which I judge him. I speak here of an innate ability that is only given to a special few, that of uncanny anticipation and the genuine gift of being virtually simultaneous in the co-ordination of mind and action. From what I have seen and heard, I believe that Locche places nearer than anyone to that phenomenal Australian wastrel, Young Griffo. Indeed, Nicolino might well have been Griffo’s modern equal. I am talking about a gift that is eternal and somehow survives natural erosion and self-inflicted damage. Griffo was a drunk for most of his life, yet never lost the ability to instinctively dodge bullets. He could pick flies out of the air. He dodged a spittoon thrown by Mysterious Billy Smith when it was almost upon him. Spotting the projectile in the bar room mirror, the well-oiled Griffo moved his head by the required fraction and carried on boozing.

Boxing has seen many runners and jumpers and contortionists who can bend their bodies every which way in almost cartoon-like fashion. These are great gifts in themselves and I give these men every credit. But their talent is generally finite. Their speed eventually diminishes and their elasticity loses its stretch. Then there are those whose special talents can turn all sorts of twisting corners but cannot handle a sudden roadblock. Whatever else one thinks of Naseem Hamed, he possessed astonishing reflexes and lightning speed. But in the one true acid test of his career, he failed disastrously to change horses in mid-stream against wily Marco Antonio Barrera. Cunningly fighting against type, Barrera embarrassed Hamed in the way that Hamed had embarrassed so many others.

So who else belongs up there with Locche and Griffo among the quick, the clever and the eternal? One lives in fear of leaving out any obvious candidates in these circumstances, but those who spring readily to my mind are Wilfred Benitez, Jem Driscoll, Bob Fitzsimmons, Joe Gans, Jack Johnson, Benny Leonard, Jem Mace, Kid McCoy, Packey McFarland, Willie Pep and Pernell Whitaker. These, for me, were the enduring aces equipped with built-in radar.

Wilfred Benitez, at his young and glorious best before his troubles drowned him, was a precocious wonder of the age. It was no surprise that he befuddled Antonio Cervantes in much the same manner as did Locche. There was nothing tacky or exaggerated in Wilfred’s nickname of El Radar. Much like Locche and Griffo, Benitez was a master of perhaps the most difficult of the fistic arts, that of moving whilst appearing to stand still. Kid Lavigne, even as he was thrashing punches into no man’s land, swore blind that Young Griffo did little more than twitch. Benitez at his best came close to occupying that rare stratosphere. I have always believed that the wiry Puerto Rican ace, if his mind hadn’t already been unravelling from personal strife, would have racked up more points than Sugar Ray Leonard in their clash of the gifted titans.

Jem Driscoll, the great ‘Peerless Jim’ was another wizard who could give an excellent impression of a ghost. American fight manager Charlie Harvey couldn’t say enough about the Irish magician who drove top men like Abe Attell and Leach Cross to near despair. “Jem Driscoll was the greatest boxer the world has ever seen,” Harvey said in his later years. “You will recall that when Driscoll boxed Attell, he outboxed the Yankee four ways from the jack. He made Attell miss so badly that Abe almost plunged through the ropes. That will give you an idea of Jem’s boxing wizardry. You may talk about George Dixon, Young Griffo and their likes as masters of the profession. But give me that boy Driscoll. He unquestionably is the king of them all.”

Bearing Driscoll’s brilliance in mind, what are we to make of Jem Mace, who retained his remarkable powers of co-ordination right to the end? As an ageing veteran, long after his Prize Ring prime, Mace fought an exhibition with Driscoll which was witnessed by a number of British boxing reporters. They couldn’t believe what they saw. Driscoll, for all his evasive trickery, couldn’t avoid being hit by Mace’s left jab.

The marvellous, natural gifts of Bob Fitzsimmons and Jack Johnson have been much more greatly documented down through the years because of our timeless fascination with the heavyweights. To those who know their stuff, Fitz still gets the vote as possessing the most brilliant boxing mind the game has ever seen. He was acknowledged as the ultimate master by the formidable triumvirate of Griffo, Kid McCoy and Joe Gans. Fitz took his natural gifts to an even higher plane by constant study of physical and mental technique. He was probably the hardest pound-for-pound hitter that ever lived, yet his hammer-like blows were delivered with finesse and often in the manner of a gentle caress.

“Fitzsimmons was the greatest short punch hitter I ever saw,” said Jim Jeffries. “He could sure snap them in with a jar. You remember how everyone thought he knocked Corbett out with a solar plexus punch? Well, old Fitz told me years afterwards that he didn’t hit Corbett in the pit of the stomach at all. He got Corbett to leave an opening, shifted and just stiffened his left arm out and caught Corbett on the edge of the ribs on the right side of the solar plexus, to drive the ribs in with the punch.”

It was Kid McCoy’s contention that a prime Fitzsimmons would have had little trouble in taking Jack Johnson. Well, folks, we can argue about that one forever and a day. I hope Galveston Jack’s star isn’t diminishing among the younger set, because we surely have enough proof now of his genius. He was incredibly quick and thoroughly schooled in every element of the game. He could slip, feint and block punches, often catching them in mid-flight. His mental powers matched his great physical strength, often to the point of shredding the other man’s patience and driving him to swing and slash at the elusive target like a rank amateur. Fireman Jim Flynn quickly reached the end of his tether against Johnson, resorting to a comical jumping and butting routine that made mischievous Jack smile even more.

Kid McCoy, like Locche and Griffo, was another blithe spirit to whom boxing came easily. A deep thinker and philosopher and a master of mind games, the Kid worshipped at the altar of Fitzsimmons and extracted all the knowledge that Freckled Bob was willing to impart. A majestic boxer and a powerful puncher, McCoy played boxing as chess and had the grand master’s gift of constantly being three or four steps ahead. Alas, the Kid’s hyperactive and analytical brain did him in at the age of sixty-seven, when it calculated that there was no reason left to live and commanded its owner to commit suicide.

The lightweight division, of course, has spawned countless men of subtle skills and varying gifts, but the three all-time masters in cleverness, in this writer’s opinion were Joe Gans, Benny Leonard and Packey McFarland. What did they have over the others? The more appropriate question might be, “What DIDN’T they have?” Writer T.P. Magilligan memorably described Gans thus: “He is the embodiment of all that is graceful and artistic in ring circles. In point of grace, action, intelligence, contour, speed and punching power, this Gans is in a class by himself.”

Was Gans cleverer than Benny Leonard? It is impossible to say, since brilliant Benny was so similarly gifted. There was no greatly discernible weakness in either man’s make-up. Their balance was superb and they were always ready to hit from any position. They could see openings almost before they presented themselves and then deliver accurate and educated blows with wonderful timing. With power and artistry, they could dismantle their opponents from any range. Leonard did indeed care deeply about getting his prized hair mussed. But Benny could rough it when the occasion demanded. He turned a potential defeat against Richie Mitchell into a thrilling and courageous victory at Madison Square Garden.

Packey McFarland, the wonder from the Chicago stockyards, the man who was never world champion yet lost just one of more than a hundred fights, was another natural. Those who saw McFarland in action never forgot him. Huge crowds marvelled at the hard-hitting, ghost-like maestro who possessed the visual tricks and elusiveness of a shadow. When McFarland exploded onto the world stage at the Mission Street Arena in Colma, California, in the spring of 1908, he was hailed as a boxing wizard without a discernible fault. Former lightweight champion Jimmy Britt was scientifically bewildered and battered to a sixth round knockout defeat and everyone was talking excitedly about the new kid on the block. Ringside reporter Eddie Smith wrote of Packey: “McFarland is everything, a hitter, a boxer, a good general and wonderfully clever and fast.”

The shame of Pernell (Sweet Pea) Whitaker’s magnificent career is that the tides of changing times forced him to display his championship wares in Las Vegas instead of more traditional and appreciative theatres. His silky artistry was deemed ‘boring’ by the new wave of ignoramuses and dilettantes whose perception of a good fight is twelve rounds of blood and thunder all the way. Idiots! They are every reason why I constantly yearn for Madison Square Garden to charge back in earnest and reclaim its mantle as the Mecca of boxing. Look at the officials’ scorecards in Sweet Pea’s title bouts. Such was his dominance at the peak of his career, he won by ridiculously lopsided margins. He was a wee genius of extraordinary speed, skill and reflexes. Pound for pound, on his very best night, he would surely have ghosted his way around most of his fellow greats.

I wouldn’t have much of an argument with anyone who wants to tell me that Willie Pep was the greatest, purest boxer there ever was. Lord knows, Willie was great enough after his famous plane crash of 1946. Before that near tragic event, however, it seemed he was a phenomenon from another planet. In those early golden days, only Sammy Angott, a notoriously difficult opponent for anyone, was able to spoil and hustle a route through Willie’s confounding exclusion zone. Pep had raced to 63 straight wins before that first loss. “Willie Pep was the greatest boxer I ever saw,” said our dear departed pal, Hank Kaplan. “There’s nobody even close to him today.”

Frustration

It is Kaplan who rather neatly brings us back to Nicolino Locche. When Hank was still ticking and giving us his great thoughts on the game, he loved Locche. Kaplan was never one to grow old or misty-eyed, and consistently gave credit to fighters of all generations. It was a source of great frustration to him that Locche’s great talents were going largely unrecognized. Boxing analyst, Curtis Narimatsu, who got to know Kaplan well, told me, “Hank absolutely adored the artistic Locche, as opposed to the blood-thirsty warlocks who favour the KO killers. Hank lamented to me often about the overlooked Locche. Nicolino had an exquisite defence and great vision.”

Nicolino Locche came from a humble background in the Tunuyan, Mendoza region of Argentina and he learned how to be untouchable in more ways than one. He had his first amateur fights as a tender nine-year old and was a crafty natural from the outset, fighting in tough little arenas that were sometimes lit with kerosene lamps when the electricity supply failed. On one occasion, against a much bigger opponent, the cheeky little Locche blew out the lamps to even up the odds!

My good friend George Diaz Smith, who has penned many a fine article about the South American masters of the game, says of Locche, “He was a contortionist by trade, miffing many a fighter to fall right into him in avoidance of fatigue and despair – with the astute twist of his upper torso and hands at his sides, swiftly jerking his head a centimeter, dodging a lead or counter-punch by half an inch and then viciously contorting the facial features of his opponent like an artist strokes his brush.

“Fighting him was like a phantom before you, and if you did see him a moment where you thought he was standing, he suddenly disappeared right before your eyes and would then be standing in another position. There was no clowning around in there with him, although he was tagged the Charlie Chaplin of boxing for his unique moves in the ring. Acquiring the taste for gamesmanship and pizzazz, Locche found that boxing was as much an entertainment measure for incorporating theatrics that no other boxer had thus far seen on the planet – not since the smaller weights in Willie Pep and Benny Leonard.

“Talk about being inventive! Locche would constantly re-invent and challenge, making boxing improvisational fun to a newer boxing realm. Sliding his feet and camouflaging the moves were just for starters. He was deadly accurate with his volume punching, which left his opponents with so much buckshot, that it would be astounding as to how they could keep up, much less continue.

“Nicolino’s manager, Tito Lectoure, always held Locche above all his prized disciples without a second thought. Lectoure said, ‘I believe Locche was the last grand idol of the Argentine fighters. He was the most spectacular that stepped into the ring. There were a lot of good fighters, but Locche was unique, standing alone. His battles weren’t bloodbaths or particularly violent, yet he always filled Luna Park with 20,000 fans and it didn’t matter who he fought. People just wanted to see him.’”

High Praise

Just recently, I came across some high praise indeed for Nicolino Locche. Not from a fellow writer, not from a manager or a trainer, but from an erudite fan who quite obviously knows his boxing. Sadly, he didn’t reveal his true identity. But his comments, in my view, deserve greater exposure and here they are: “As a lover of boxing and avid reader of boxing history, it may come as a bit of a surprise to you that I don’t place much weight on the opinions of boxing ‘historians’ when it comes to evaluating and comparing fighters. This holds true even for such veteran observers as Nat Fleischer, who personally saw every major boxing champion compete in person since the days of Jack Johnson through the era of Ali. That isn’t to say I completely dismiss everything Fleischer has to offer from his recollections, but he was, after all, just one man sitting ringside.

“However, there is one man whose opinion on the great fighters I regard with extreme deference; that man is former trainer Ray Arcel. No musty relic of the past, Arcel may have gotten his start in boxing as a sparring partner for the legendary lightweight Benny Leonard in the early 1920s, but over his 70-year career in boxing Arcel trained and developed championship fighters all the way through Roberto Duran and Larry Holmes. In between, world champions from Ezzard Charles to Barney Ross to Kid Gavilan and more than a dozen others all learned their trade at the knee of the master. So when Ray Arcel talks about fighters, I listen closely, because Ray Arcel might well be the greatest boxing mind in history.

“Most boxing historians will tell you that perhaps the greatest defensive fighter in history was the legendary Willie Pep, a magnificent featherweight champion universally included on every boxing wag’s all-time pound-for-pound list of the greats. On film, Pep is almost comically elusive and difficult to hit cleanly, seeming to anticipate incoming blows by telepathy and move just an inch out of range before countering sharply. So slippery was Pep in the ring that legend has it he once won a round against contender Jackie Graves without throwing a single punch (the reality is a bit different, but Pep certainly had Graves flailing and stumbling in vain in a desperate attempt to land a punch).

“So when Ray Arcel said that Willie Pep was only the second greatest defensive fighter he’d ever seen, I sat up and took notice. Who could Arcel’s number one be? The great Benny Leonard, of whom it was said he could box an opponent’s ears off for 15 rounds without ever getting his hair mussed? The furiously weaving Duran, whose frenetic movement and relentless aggression made him a miserable target? Jack Johnson? Wilfred Benitez? Could it be Ali?

“No. The man Ray Arcel claimed was the greatest defensive boxer he’d ever seen was a little known Argentinian junior welterweight by the name of Nicolino Locche, a former world champion with more than 100 career victories who was none the less almost completely unknown to American boxing fans because he fought exclusively in South America.

“Locche trained lazily. He lacked a punch. He smoked up to 50 cigarettes a day. Heck, he smoked cigarettes in the ring between rounds! And despite all this, Nicolino Locche was quite possibly the most brilliantly defensive fighter in the history of boxing. Like Pep, Locche could stand in the center of the ring, hands at his sides, and openly laugh as his opponents tried desperately to land a solid punch, each effort missing by just an inch as Locche just barely moved out of harm’s way.”

Now, Ray Arcel didn’t know everything of course, as I’m sure our anonymous friend would be quick to concede. But foxy old Ray sure as hell knew more than most others.

Full Circle

At the end of it all, I still find myself coming back to Young Griffo and Nicolino Locche as the true, natural born instinctive masters. There is a much easier slide rule for measuring such men: a certain indifference and indeed a degree of arrogance on their part as to just how brilliant they are.

One occasionally meets such people. They are the people who enthrall you and infuriate you simultaneously. They will hit a home run or belt a golf ball 300 yards at the first time of asking and then trot off to do something more interesting. Griffo liked to drink and Locche liked to smoke. But why not win a few major boxing titles in between? After all, Bobby Jones made a rewarding little pastime out of golf.

• Mike Casey is a boxing journalist and historian.. He is a member of the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO), an auxiliary member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and founder and editor of the Grand Slam Premium Boxing Service for historians and fans (www.grandslampage.net).