by Pavel Yakovlev – Greg Page, the World Boxing Association heavyweight champion in 1984-85, was arguably the best heavyweight of the 1980s outside of Larry Holmes and Mike Tyson. If the heavyweights of that era are compared based strictly on their best performances, it is easy to envision Page beating almost all of his contemporaries. Page had everything as a fighter with the exception of consistency. For this reason, too many fans judge Page based on his off-nights and losses that occurred after his peak years. Consequently, the boxing world has too often blinded itself to the reality of just how good Page could be.

by Pavel Yakovlev – Greg Page, the World Boxing Association heavyweight champion in 1984-85, was arguably the best heavyweight of the 1980s outside of Larry Holmes and Mike Tyson. If the heavyweights of that era are compared based strictly on their best performances, it is easy to envision Page beating almost all of his contemporaries. Page had everything as a fighter with the exception of consistency. For this reason, too many fans judge Page based on his off-nights and losses that occurred after his peak years. Consequently, the boxing world has too often blinded itself to the reality of just how good Page could be.

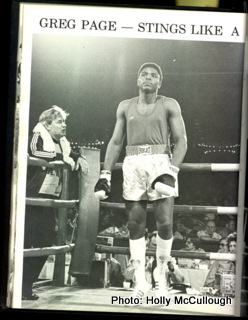

During his 21-year career, Page accumulated a record of 58-17-1, including 48 kayos. Most of Page’s losses took place after his prime, which was 1981 to 1985. At his peak, Page was usually ranked in the top four or five worldwide. Matched constantly against the best opposition of his era, Page generally emerged victorious: Gerrie Coetzee, Renaldo Snipes, James Tillis, and Marty Monroe being among the fighters he beat. In 1983-84, in fact, some experts believed Page might have defeated the aging Holmes if given the opportunity.

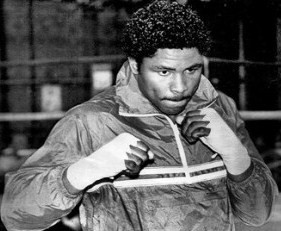

Without doubt, Page’s natural ability was extraordinary. Standing 6’2” and weighing 223 to 240 lbs., Page was athletic, strong, durable, and fast, and he carried one punch knockout power in both hands. He had a strong chin and could absorb a heavy wallop with impunity.. Page’s hand and foot speed were exceptional, and he had an excellent left jab. Comparisons between Muhammad Ali and Page were common, as Page often danced circles around opponents while spearing them mercilessly with jabs. Page’s body movement was unusually fluid, enabling him to evade punches effortlessly. When Page unleashed combinations, he could be devastating. Observers sometimes remarked that Page fought like a heavyweight version of Sugar Ray Leonard.

In some ways, Page was comparable to the 1930s heavyweight champion Max Baer, in that both are remembered as potentially near-great fighters who enjoyed playing in the ring, and who did not actualize their full ability over the long-term. Baer and Page beat many of the best heavyweights of their era, and each lost numerous bouts he should have easily won. Baer and Page are alike in that both won high-stakes bouts against dangerous opponents associated with controversial political systems. Baer defeated Max Schmeling, who hailed from Nazi Germany; Page kayoed Gerrie Coetzee, a native of apartheidist South Africa. Interestingly, after winning the world championship, Baer and Page were both dethroned in their first defense, inexplicably losing to inferior opponents.

Baer was eventually inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame and the World Boxing Hall of Fame, despite not achieving truly great status as a champion. The rationale for inducting Baer is logical: if we ignore his numerous fluke losses and judge him strictly on his best nights, Baer was excellent. What then, about Page? Based on the logic that justifies Baer’s inclusion in the Halls of Fame, someday Page should be inducted as well. After all, Page was a better fighter than many heavyweights already inducted into the Halls of Fame. The question is, how soon will the world be ready to judge Page based on how well he boxed in his best fights.

In this article, ESB reviews a quarter century of Page’s career, chronicling his progress from the amateurs to the world championship to his final bouts as a middle-aged boxer.

FAMILY BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION TO BOXING

Page was born on October 25, 1958 in Louisville, Kentucky. He grew up in Louisville’s Beecher Terrace housing project; his father Albert supported the family by working as a bus driver for the city. A life-long resident of Louisville, Albert was from the city’s east end, known as Smoketown. During the 1960s, the Pages often watched live broadcasts of two other Smoketown natives who achieved boxing stardom: Muhammad Ali and Jimmy Ellis. Just several years older than Ali and Ellis, Albert knew both boxers in their youth. No doubt, Albert’s kinship with the fighters influenced his sons. Greg and his brothers thus felt an intensified sense of connection to the bouts they saw on television.

Page was born on October 25, 1958 in Louisville, Kentucky. He grew up in Louisville’s Beecher Terrace housing project; his father Albert supported the family by working as a bus driver for the city. A life-long resident of Louisville, Albert was from the city’s east end, known as Smoketown. During the 1960s, the Pages often watched live broadcasts of two other Smoketown natives who achieved boxing stardom: Muhammad Ali and Jimmy Ellis. Just several years older than Ali and Ellis, Albert knew both boxers in their youth. No doubt, Albert’s kinship with the fighters influenced his sons. Greg and his brothers thus felt an intensified sense of connection to the bouts they saw on television.

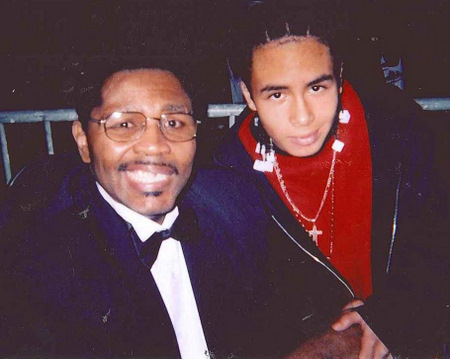

In an interview for this story, Dennis Page, Greg’s older brother, discussed the link between Smoketown and his family. One interesting anecdote occurred in the Bahamas in 1981, when Greg boxed on the undercard of Ali’s match with Trevor Berbick. The Pages and family friend Wellington Guess (a Smoketown native known as Mr. Boney) encountered Ali at the airport after the fight. “We were getting our luggage, then we see Ali,” explained Dennis. “Suddenly Ali looked in our direction and spoke first…he shouted ‘What’s goin’ on Bone?’ That just blew Greg and me away. We were amazed. We never knew that Ali and Mr. Boney knew each other that well.”

Page began boxing at the age of 12, following Dennis’s example. “I started boxing, then Greg started boxing,” said Dennis. “Billy Martin Sr. was our first trainer; he had a gym in New Albany, Indiana. Daddy would drive us over the river to Billy Martin’s gym. We trained there for two years.” Eventually, the Pages learned about a boxing gym much closer to home, run by Leroy Edmerson. “Leroy was training guys out of a basement in Beecher Terrace, on Baxter Street. Somebody told Daddy about Leroy. I was in the air force by then, but Greg was boxing, so that’s when Greg switched to Leroy.” Edmerson’s club was known as the Baxter Street gym.

Edmerson’s empathic and skilled mentoring deeply impacted Page, who was 14 when he joined the Baxter Street gym. In fact, Edmerson’s support may have prevented Page from quitting boxing while still an adolescent. According to Dennis, “At first, Greg was a too easy going in Leroy’s gym. The other kids were a little too hard on him. So Leroy took Greg out of the gym, and took him to his attic to work in private. They worked alone for about six months. After that, Greg went back to the gym, and he was like new. He was a force to be reckoned with.”

During his teenaged years, Page was not arrogant or edgy; rather, he was known for being unassuming and friendly. He even used his boxing skill to protect other children. According to Dennis, “Anyone could approach Greg and talk to him, even when he got big. Greg had this thing about people being picked on…he always protected the underdog. Once, when he was in ninth grade, Greg was playing basketball with the seventh graders. Some older kids, bullies, went onto the court and stole the ball. They kicked the ball into the middle of Muhammad Ali Boulevard. Next, one of them mugged Greg’s head, and took a swing at him. But Greg just swung back and knocked the kid out. From that time on, Greg was the hero of the seventh graders.”

An avid athlete in high school, Page was deeply involved in basketball as well as boxing. Eventually, however, Albert demanded that Page commit himself to one sport. “Greg was playing basketball for the high school team. One day Daddy told him he’s going to have to make a decision about which sport to play: basketball or boxing,” said Dennis. “Daddy said to Greg, which sport will it be…are you going to box or are you going to box?”

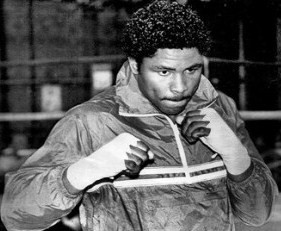

THE AMATEUR BOXING PRODIGY

Now focused solely on boxing, Page established himself as one of the best amateur heavyweights in the nation. Before long, the world knew that a new boxing prodigy was fighting out of Louisville. Page’s talent was such that the media often compared him to the young Muhammad Ali. In December 1976, Ali — then the world heavyweight champion — gave his fellow Louisville native the honor of fighting an exhibition match. 1,200 fans turned out for the event, after which Ali declared that Page was “championship material.”

Now focused solely on boxing, Page established himself as one of the best amateur heavyweights in the nation. Before long, the world knew that a new boxing prodigy was fighting out of Louisville. Page’s talent was such that the media often compared him to the young Muhammad Ali. In December 1976, Ali — then the world heavyweight champion — gave his fellow Louisville native the honor of fighting an exhibition match. 1,200 fans turned out for the event, after which Ali declared that Page was “championship material.”

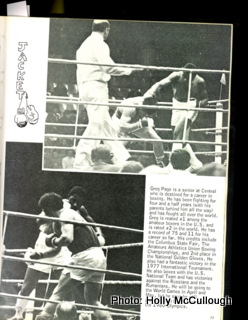

Page’s accomplishments during this period validated Ali’s judgment. In 1975, Page advanced to the quarterfinals of the National Golden Gloves, a remarkable achievement considering that he was barely 16-years-old. A year later, Page reached the semifinals of the same tournament, losing only to highly touted Michael Dokes. Page won the National AAU tournament in 1977, repeating the feat in 1978, during which he also won the National Golden Gloves. Page also achieved international stature, fighting regularly on television against tough, experienced boxers from the Iron Curtain countries. He defeated several of the Soviet Union’s best fighters, including Igor Vysotsky, Viktor Tereschenko, Piotr Zayev, and Koren Inzheyan. In 1978, Page knocked out Romania’s Mircea Simon, an Olympic silver medallist.

The 1977 win over Vysotsky may have been the grand achievement of Page’s amateur career. At the time, the power punching Vysotsky was one of the world’s most feared amateurs. Just a year earlier, Vysotsky had scored a one-sided knockout over Teofilo Stephenson, the legendary Cuban who won three Olympic gold medals. However, Vysotsky could barely land a punch against Page, who used airtight defense and nimble counterpunching to win an easy decision.

Meanwhile, as the world’s best amateur fighters regarded Page with growing respect and dread, the youngsters at the Baxter Street gym related to him with affection. To these boys, Page was a hero and protector of neighborhood kin.

Kelley Mays, who is now a trainer in Kentucky, started boxing at Edmerson’s gym at the age of 11. Mays spoke about Page (who was four years older than May), with profound feeling and respect. “My mother trusted me with Greg, she didn’t trust me with anyone else,” Mays reminisced. “Greg would drive me to the gym, and then drive me home. When my mother knew Greg was with me on trips, she felt I was safe. He took care of us. I was raised by just my mother. I had no father. Greg made a difference.”

Interestingly, Mays recalled that the teenaged Page liked to enjoy himself in training, to experience the feeling boxers call “fighting happy.” Mays’s recollections of Page yield insight into the boxer’s later ring persona, that of the taunting and arrogantly self-assured champion known to sports fans worldwide. “Leroy would line-up the kids in the gym, fifteen deep, and let them take turns pounding Greg’s body,” explained Mays. “Greg would hold his hands up, like he was champion. At the same time, Greg would dance and clown as the kids hit him with body shots, one kid after another. This would go on 45 minutes to an hour. We’d hit him with our best shots, and he would just laugh. It was like conditioning with a medicine ball. While this was happening, Greg would dance, he would shuffle, he would have fun. Greg loved to play in the ring. He loved to do that. Sometimes he was like a cross between vaudeville and disco.”

Page’s goal was to win the gold medal at the Olympic Games, scheduled for the summer of 1980 in Moscow. Cold War politics, however, scuttled Page’s dream. When the USSR intervened militarily in Afghanistan in 1979, the United States boycotted the Moscow games. His Olympic dreams thwarted, Page decided to turn professional. His final amateur record was 90-11 (55 kayos).

EARLY PROFESSIONAL YEARS

In February 1979, Page fought his first professional fight, stopping Don Martin in two rounds. He won all seven of his fights that year by knockout. Page continued with the same team that guided him as an amateur: his father Albert served as manager, Guess functioned as an advisor, and Edmerson handled training. As described by Dennis, the trio “formed the nucleus of everything.” Apparently Albert intended to maneuver his son without signing an exclusive contract with any single promoter. Butch Lewis staged Page’s early fights, and soon Don King had a concurrent contract to promote the fighter as well. Before long, King and Lewis were competing fiercely to handle Page.

While Albert juggled promoters, Page took care of business in the ring. In 1980 he won six fights, several of the wins coming against tough, well-known clubfighters. Page knocked out hard punching Larry Alexander (16-7-2; 16 kayos) in six rounds. He stopped Leroy Boone (13-5; five kayos), a brick chinned fighter known for being hard to kayo. In a difficult tactical bout, Page decisioned cagey George Chaplin (16-1-1; eight kayos) in ten rounds. Beating these opponents put Page on the short list of boxing’s hottest up-and-coming heavyweights.

Page started fighting top-flight opposition in 1981. First came Stan Ward (13-3-2; six kayos), a hard-hitting fringe contender from California. Page gave Ward a beating, dominating the bout with hand speed and combination punching. Ward fought gamely, but he retired at the end of the seventh round with a swollen eye. Consequently, Page was ranked in the worldwide top ten by the sport’s two sanctioning groups, the World Boxing Association (WBA) and the World Boxing Council (WBC).

Next, Page met his first world-rated opponent in Marty Monroe (23-1-1; 15 kayos), a boxer-puncher with a dangerous right hand. Page won easily; his hand speed and power proved too much for Monroe to withstand. After five rounds, Monroe’s corner wisely retired their fighter. Page’s impressive, nationally televised victory over a “name” opponent raised his public profile to new heights. Now recognized as a legitimate top contender, Page was often portrayed in the media alongside Gerry Cooney and Michael Dokes as one of a trio of young, undefeated heavyweights who could someday challenge Holmes for world supremacy.

One month after the Monroe fight, Page’s life changed dramatically when his father died of lung cancer. Only 45 years old, Albert’s symptoms first appeared shortly before his death. The loss to the Page family was sudden and shocking. “We all took it hard when Daddy died,” stated Dennis. “We had never experienced that kind of loss before. Our grandparents were still alive. It was a new experience for us, losing someone like that. It really shook Greg. Daddy was always there to tell him what to do. That strength he got from Daddy was gone.”

Albert’s death also led to a decisive change in Page’s arrangement with promoters. Don King quickly emerged as Page’s exclusive promoter, and the relationship determined Page’s career prospects for most of the 1980s. Although Page benefited from King’s ability to secure major fights, at least one journalist – Jack Newfield of the New York Post — wrote that within several years, Page became disillusioned and demoralized by the financial realities of the promotional contract (see Newfield’s “Only In America: The Life and Crimes of Don King”). Whatever the truth, Page felt the consequences of signing with King immediately, as Butch Lewis sued King and the Pages for alleged business interference. King countersued, and a settlement was not reached until several years later.

But for now, personal loss and contractual headaches had no effect on Page’s ring performances. Now fighting regularly on Don King Productions cards, Page continued his winning ways. In June 1981, he scored a devastating second round knockout over hard-brawling veteran Alfredo Evangelista (40-5-3; 29 kayos). A few months later, Page decisioned George Chaplin in a rematch. He finished the year by stopping rugged Scott LeDoux (28-9-4; 18 kayos) in just four rounds. Page kept his streak into 1982 when he handily defeated former top contender Jimmy Young (30-10-2; ten kayos), winning over 12 rounds by unanimous decision.

HEIR APPARENT TO THE WORLD CHAMPION

Page’s future now seemed unlimited. Only 23-years-old and undefeated in 19 fights, Page was just entering his prime. Many pundits, in fact, now favored Page to beat anyone outside of Larry Holmes. During this period, Page carried the aura of an heir apparent to the world’s heavyweight champion.

But market realities mandated that Page would have to wait before getting to fight Holmes. In June 1982, the sporting world was riveted to Holmes’s showdown with Gerry Cooney, the hugely popular, unbeaten heavyweight from New York. The bout, which had been hyped and promoted for almost an entire year, was the most lucrative fight in history until that time. Experts generally favored Holmes to beat Cooney, and anticipated that Page would face Holmes in the aftermath.

Intending to keep the public spotlight on Page, King scheduled a fight with Trevor Berbick (21-2-1; 18 kayos) on the Holmes-Cooney undercard. Few expected Berbick to trouble Page, even though Berbick was a tough and proven contender. But surprisingly, Berbick pounded out a one-sided decision win. The scores were 96-94, 98-92, and 98-92. Most likely, the result was a fluke, as Page broke his thumb early in the fight and was unable to effectively throw his right hand. The thumb injury was severe, requiring Page to wear a splint for a month. Nonetheless, for the first time, Page’s aura of invincibility had been tarnished.

Following a five-month layoff, Page returned to the ring in a high stakes bout against world rated James Tillis (22-2; 17 kayos). Despite being knocked down by a hard right in the second round, Page was brilliant against Tillis. By round four, Page was in control, timing his shots and shaking Tillis with counterpunches. Page dominated the rest of the fight and ultimately finished Tillis with a powerful right in the eighth round. In covering the bout for Ring Magazine, Randy Gordon was critical of Page yet simultaneously awed by the fighter’s natural ability. “Page tries to imitate Ali too much in style,” wrote Gordon. ”Hands low, dancing on his toes with arms dangling, punches which return to his waist. After lashing out with un-heavyweight like speed, pulling away from punches and showing a hard, swift right lead, all combined in a cocky, brash style that begs for someone to slap him around. But, as with the case of Ali, wanting to hit him and doing it are two different things.”

In May 1983, Page met top contender Renaldo Snipes (23-2-1; 12 kayos) in a bout to determine the mandatory challenger for Holmes’s WBC title. He defeated Snipes in impressive fashion, taking a unanimous decision by scores of 115-112, 116-112, and 115-111. Page’s footwork and hand speed were too much for Snipes, who could never score with his dangerous right hand. After the fourth round, during which Snipes’s right eye swelled shut, Page took control. Again, Page’s athleticism seemed almost preternatural; he displayed the uncanny ability to attack while simultaneously pulling away. According to Ring Magazine’s Bert Randolph Sugar, “Page alternated his style, occasionally coming in as if he were retreating on the balls of his feet to throw punches at Snipes’s exposed head and midriff, and every now and then bulling Snipes into the ropes.”

The victories over Tillis and Snipes restored Page’s credibility after the lows of the Berbick defeat. The Snipes win in particular held value, as only months earlier Snipes had soundly beaten Berbick. Having regained his heir apparent aura and finally established as the mandatory challenger for the WBC title, Page looked forward to fighting Holmes. Page’s chances against the champion seemed good, as Holmes’s recent performances revealed signs of encroaching age and declining athletic ability.

SURPRISE REVERSALS IN 1984

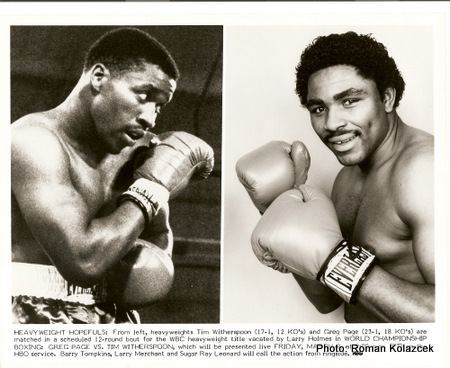

However, the Holmes vs. Page title fight would never occur. Holmes’s relationship with Don King was strained by financial disputes and the champion wanted an opportunity to break ties with the promoter. At the same time, a new sanctioning group, the International Boxing Federation (IBF) emerged when the WBA fragmented due to political strife. Hoping to establish credibility with the public, the IBF offered their vacant heavyweight title to Holmes, who accepted. In this way, Holmes spurned King’s $2.5 million offer to defend his title against Page. Consequently Page was matched against the next highest rated contender, Tim Witherspoon (17-1; 12 kayos) for the vacant WBC title. The bout was scheduled for March 1984.

Page faced a formidable opponent in this fight: the 6’3”, 220 lbs Witherspoon was one of the most dangerous and capable heavyweights of his generation. A product of Philadelphia’s ultra-competitive boxing culture, Witherspoon was durable, strong, technically sound, and possessed heavy power in both hands. Nonetheless, Page was regarded as too talented to lose to Witherspoon. The odds makers installed Page as a 9 to 5 favorite to win the bout.

But Witherspoon upset the odds and defeated Page by majority decision to win the WBC title. The final scores were 117-111, 117-111, and 114-114. Uncharacteristically, Page did not fight by dancing and boxing from center ring; rarely did he use his excellent left jab. He chose instead to fight at close quarters, often with his back against the ropes, baiting his opponent into attacking. Page, perhaps, landed more blows, but he boxed in spurts, apparently hoping to steal rounds with flurries of light punches. Witherspoon responded with a steady stream of thudding jabs and right crosses. Afterwards, Page bitterly disagreed with the verdict, feeling he had done enough to win. Witherspoon however was the more aggressive fighter, impressing the judges by landing the harder blows.

The disgruntled Page announced his retirement after the fight. As quoted by Pat Putnam in Sports Illustrated, Page stated, “He may have been more aggressive, but he sure didn’t score the most points. The hardest punches don’t make the difference. Scoring does. I don’t want to comment on the decision. I’ve been going through hell like this my whole career. This is my retirement. I’ve had enough of this bull.” A few days later, though, Page changed his mind and decided to continue his career. He also made the dramatic move of ending his professional relationships with his brother Dennis, Guess, and Emerson. Page then moved to Arizona to train under Janks Morton, who had previously coached Sugar Ray Leonard.

Despite the effort to reorient his career, the following summer Page was set back further when he lost a 12 round decision to underdog David Bey (13-0; 11 kayos) in Las Vegas. Although the fight was closely contested, the judges were unanimous that Bey had outworked and outpunched Page. After this surprising defeat, Page fell to the margins of the world ratings. Many now doubted that he had the competitive drive, natural aggression, and willpower necessary to succeed against the world’s best heavyweights. However, Page’s greatest career achievement lay just ahead of him.

TITLE WINNING VICTORY OVER COETZEE

As a result of his victory over Page, Bey became the mandatory challenger for WBA world heavyweight champion Gerrie Coetzee. South African promoter Sol Kerzner then scheduled Bey to meet Coetzee in December 1984, in Sun City, Bophuthatswana. However anti-apartheid activists in the United States urged Bey to boycott the fight, as Bophuthatswana was a faux state the South African government created to circumvent their embarrassing apartheid society. Ultimately, Bey relented, and told his promoter Don King to decline the bout. King then persuaded the WBA and Kerzner to accept Page as a substitute, and soon Page was in South Africa to challenge Coetzee.

Interestingly, over the years some fans and boxing insiders have questioned whether the wily King pulled strings to substitute Page for Bey. Although Bey had beaten Page several months earlier, he was not necessarily the better fighter. The strong but plodding Bey was inexperienced (he had only 14 professional bouts at the time) and hittable, qualities that made him vulnerable against the hard-punching champion. On the other hand, Page had the experience, skill, and fighting style to beat Coetzee. King wanted to take control of the WBA belt, so he had incentive to send his best heavyweight into the ring in Sun City.

Because of his lackluster efforts against Witherspoon and Bey, Page no long carried the aura of a nearly unbeatable fighter. Oddsmakers installed Coetzee as a heavy favorite to win the fight. At the time, the 29-year-old South African was at this peak, having won the WBA title a year earlier with an impressive knockout over Mike Dokes. At 6’3”, 220 lbs, Coetzee was a dangerous stand-up boxer with kayo power in both hands, especially his right. The champion had already proven his mettle in numerous bouts against world-class opponents.

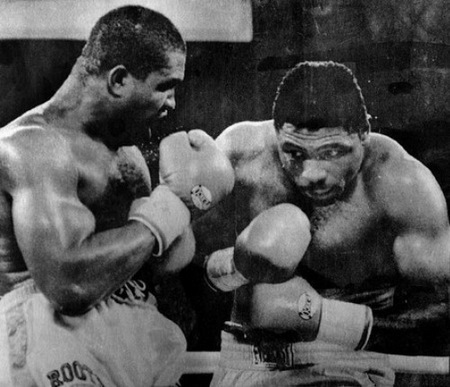

From the opening bell, the fight was a brawl, fought mostly in the center ring with both fighters exhibiting excellent stand-up boxing technique. Page was the quicker, more fluid boxer, particularly on his feet; his slippery head movement was especially effective. In contrast, Coetzee was trickier and harder punching, constantly feinting and throwing powerful right crosses, most of which narrowly missed Page. As early as the first round, it was obvious that Coetzee was loading up with his explosive right hand, hoping to connect with a fight-ending punch. The champion won the first two rounds by connecting occasionally with heavy rights and left hooks; Page prudently kept out of trouble by jabbing and moving.

But Page’s confidence increased as a result of withstanding Coetzee’s bombs. In the third round, he traded punches with the champion. The tide of battle changed midway through the round when Page stunned Coetzee with a left hook, knocking his mouthpiece out. Moments later, Page noticeably hurt Coetzee with another left hook. Although Coetzee fought back effectively with right hands, he was exhausting himself by attempting too many powerpunches. It looked as if the champion felt psychologically vulnerable and needed to compensate with excessive aggression. In between rounds, Coetzee was breathing heavy and showing signs of fatigue; Page, in contrast, appeared relaxed.

In the fourth and fifth rounds, the tempo of the fight slowed, as both boxers conserved strength. They traded jabs on even terms, the pattern altered only when Coetzee missed with powerful rights. In the fifth, the jabbing contest continued, but now Page was out jabbing Coetzee. The champion reacted by firing more right hands, but Page’s elusive head movement caused Coetzee’s swings to constantly miss. By the end of the fifth, Coetzee looked tired while Page appeared to have taken control of the fight.

Coetzee increased his aggression in the sixth round, unleashing torrid combinations of power punches. Page was stunned by two heavy rights and forced onto the defensive. But Page quickly recuperated and connected with a strong right: Coetzee’s legs wobbled and he was seriously hurt. For the remainder of the round, the champion clinched while Page controlled the action with flurries. At the sound of the bell, Page landed crunching right, and in the following seconds, Coetzee slumped to one knee. Although a knockdown was not ruled (Coetzee’s fall was a delayed reaction after the bell) and Coetzee regained his feet, the champion was obviously tired and weakened.

Sensing an opportunity to win by knockout, Page opened the seventh round aggressively. He quickly hurt Coetzee, who fell to one knee after taking two rights. As the referee tolled the count, Coetzee looked so beaten it was hard to imagine he would arise. But amazingly, Coetzee got up and unleashed his most ferocious assault of the fight. Soon, a right stunned Page and forced him backwards. The fighters then engaged in their most intense, dramatic exchange yet, each connecting with hurtful left hooks and rights to the head. Coetzee gained the upper hand; his furious attack soon trapped Page in a corner. However Page defended well; he slipped many punches, and recuperated quickly whenever hit. Inevitably Coetzee’s energy flagged and his attack lost momentum. Page then maneuvered the action back to center ring, where both fighters rocked each other with big right hands.

For the first half of the eighth, both boxers jabbed cautiously, trying to recoup energy. When Coetzee resumed his right handed attacking strategy, his punches missed by wider margins than usual. The champion was obviously spent and vulnerable. Late in the round, Page made his move: a right to the temple buckled Coetzee’s legs. Page followed with two more rights and a left hook that knocked Coetzee flat on his back. The champion was out cold, never stirring as he was counted out. The exuberant Page leaped high off the floor: he was the new WBA heavyweight champion of the world.

WORLD CHAMPION IN 1984-85

The decisive win over Coetzee atoned for Page’s losses to Witherspoon and Bey. Once again, the media and public recognized Page as an emerging great fighter, a boxer who could potentially defeat Larry Holmes. Now the WBA heavyweight champion of the world, Page was on the verge of actualizing his true potential. His earlier failures were written off as aberrations: the result of poor mental focus, tactical mistakes, or (as in the Berbick fight), fluke injury. Many observers expected Page’s title reign to be a long one.

The decisive win over Coetzee atoned for Page’s losses to Witherspoon and Bey. Once again, the media and public recognized Page as an emerging great fighter, a boxer who could potentially defeat Larry Holmes. Now the WBA heavyweight champion of the world, Page was on the verge of actualizing his true potential. His earlier failures were written off as aberrations: the result of poor mental focus, tactical mistakes, or (as in the Berbick fight), fluke injury. Many observers expected Page’s title reign to be a long one.

Page’s first title defense took place in April 1985, against former amateur rival Tony Tubbs (20-0; 14 kayos). The 6’3”, fast and tricky Tubbs had recently established himself as a contender by decisioning James “Bonecrusher” Smith. But few expected the challenger to trouble Page. Although Tubbs was regarded as an exceptional talent, his conditioning and motivation were suspect. In addition, Tubbs was not a heavy puncher, and professionally he was relatively inexperienced. Most telling, as amateurs Page had beaten Tubbs in six of their seven meetings. Thus, Page was a solid favorite to retain his title.

However, to everyone’s surprise, Tubbs outboxed Page and won a unanimous decision. The final scores were 145-140, 145-142, and 147-140. Looking sluggish, Page did not make full use of his own boxing skill and was suckered by Tubbs’s slick tactics. For example, Tubbs often leaned backwards, making Page reach with the left jab; Tubbs then countered with fast, light rights as Page dropped his left during the recoil. Tubbs steadily stole points by landing slapping blows; the bout thus seemed like a contest between thinkers rather than a struggle between athletes in a contact sport. J. R. Jowett of Ring Magazine observed, “The two were certainly boxing skillfully, and the bout was an intricate chess match of setups and counters. But it lacked something…namely, excitement. Perhaps the contestants were too familiar from amateur meetings.”

Complacency may have been a factor in Page’s performance. Although no heavier for Tubbs than he had been for several prior fights (239 ½ lbs.), Page’s physique looked fleshier than usual, prompting ringside observers to question his conditioning. Fans in Buffalo, where the bout took place, reported that Page spent a lot of time playing basketball before the fight, rather than working out in the gym. Again, the public and media sensed that Page lost a bout he would have won had he only been more active. The Associated Press described Page’s effort as “lackadaisical.”

Kelley Mays believes that Page was overconfident and did not regard Tubbs as a serious threat. “I don’t think that either one of them took the fight serious”, said Mays. “Each one thought they had the upper hand over the other because of their amateur experience. Each guy thought he had the other’s number…they both took each other too lightly. Neither guy trained hard, because each thought he would win. Greg put on a sluggish performance.”

POST CHAMPIONSHIP YEARS

Page remained inactive for the rest of 1985. When he resumed his career in January 1986, he suffered another surprise defeat. The opponent was James Buster Douglas (20-3-1; 15 kayos), who won a clear-cut decision. Douglas, an unranked boxer at the time, was regarded as little more than a clubfighter (although he would latter knock out Mike Tyson in a classic upset), and Page was expected to beat him easily. As a result of this setback, Page fell from the world ratings.

The Douglas loss marked a decisive downward turn for Page. For the rest of his career, he fought as an opponent for higher ranked fighters, or in meaningless matches against low-level opposition. He never again penetrated the worldwide top ten ratings. Rarely did Page fight up to his true ability level during these years; a litany of defeats ensued. In the summer of 1986, Mark Wills (5-5-1; five kayos) shockingly kayoed Page in nine rounds. In 1990, Wills stopped Page in a rematch, this time in six rounds. Nobody associated with Page can explain these losses; he should have won both fights easily. In 1987, Page looked sluggish against Joe Bugner (60-11-1; 37 kayos), losing a unanimous decision. Orlin Norris (20-1; nine kayos) outpointed Page in 1989.

Why Page – a fighter with the potential to achieve borderline greatness – faded when he should have been in his physical and athletic prime is a mystery. Mays commented, “Were there personal issues with him, or did he lose his motivation? It’s hard to say. We would never know, because Greg always put on a happy face. If he was unhappy or if he was down on life, we could never tell. He would never let it show. He certainly never displayed it around me. I couldn’t get a negative reading.”

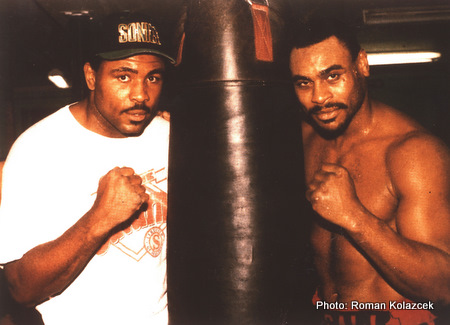

During the late 1980s, Page worked regularly as a sparring partner for world champion Mike Tyson. In a famous gym session in 1990, as Tyson was training in Tokyo to fight Douglas, Page knocked Tyson down. The incident was immediately reported internationally, and reminded the world just how good Page could be. But Page’s career was not enhanced by his gym exploits against Tyson. According to Kelley Mays, “Greg was the first to expose Tyson. He dropped him twice in sparring with 16 oz. gloves. But letting Greg spar with Tyson wasn’t a good move by Greg’s management. After those knockdowns, it meant that the champ would never give Greg a chance to fight him for real.”

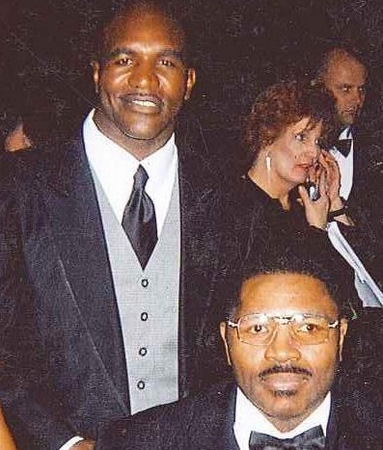

Page fought several notable fights in the early 1990s, with mixed results. Top contender Donovan “Razor” Ruddock (24-3-1; 17 kayos) stopped Page in eight rounds in a hard fought 1992 bout. Page put up excellent resistance before falling. Four months later, Page won a unanimous decision over James “Bonecrusher” Smith (33-9-1; 26 kayos). Also in 1992, Page lost a close decision to Francesco Damiami (29-1; 23 kayos). In 1993, Bruce Seldon (27-3; 23 kayos) kayoed Page in nine rounds. After the Seldon bout, Page announced his first retirement.

RETIREMENT AND COMEBACK

After retiring, Page remained in boxing, living in Las Vegas and working as a trainer. Among the fighters Page trained were Marischa Sjauw, a four time women’s world champion, and Oliver McCall, who kayoed Lennox Lewis to win the WBC title in 1994. Page, in fact, was in McCall’s corner during the Lewis bout. During these years, Page remained in excellent shape, completing his roadwork, hitting the bags, and sparring often with other professionals.

Page also attended to family matters. When not in the gym, he remained at home parenting his two daughters (his wife at the time was frequently on business trips as a Don King Productions employee). But eventually Page’s marriage deteriorated and financial stresses mounted; bankruptcy and divorce followed. Earning money by boxing seemed like a logical solution. As Page later explained (in a 2004 interview with Gary A. Johnson), “I was training fighters to beat fighters that I knew I could beat. I started fighting seriously.”

Returning to the ring in 1996, Page won a series of easy knockouts against overmatched foes in small clubs, mostly in Nashville. By 1998, Page had fought 17 comeback fights, all victories with the exception of a draw against Jerry Ballard (19-1; 19 kayos). He suffered his first comeback reversal in 1998, when he lost a unanimous decision to highly touted prospect Monte Barrett (18-0; 12 kayos). The following year, he won a rematch against former nemesis Tim Witherspoon (46-9; 32 kayos), winning a seventh round TKO in a battle of aging former champions. This win was followed by a decision loss to former contender Jorge Luis Gonzalez (29-5; 27 kayos). Months later, a severe shoulder injury compelled Page to retire in the eighth round against Robert Davis (21-0; 15 kayos). The bout was competitive despite Page’s crippling injury.

In March 2001, Page fought his final bout, facing Dale Crowe (21-4; 14 kayos) in Erlanger, Kentucky. Despite the disparity in age (Crowe was younger by 18 years) the fighters were reasonably matched. Page’s vast advantage in experience counterbalanced the youth of Crowe, who was a tough but limited journeyman at best. Yet Crowe won the fight when Page was counted out at 2:56 of the tenth and final round. Until the ending, Page was never hurt and the action was closely contested. In the final seconds of the bout, Crowe hurt Page with a heavy left and dropped him with a final flurry of punches. After the count, Page remained unconscious on the canvas. Minutes passed without a response from the fallen boxer; clearly something was wrong.

Unbeknownst to ringside officials and the attending physician, Page had suffered a hematoma (bleeding in the brain). Resuscitation equipment was missing from ringside that night. No ambulance waited on premises. It took almost 45 minutes for an ambulance to arrive at the scene. Even after taken into medical care, over two hours elapsed before doctors could start surgery on Page. During this time Page suffered brain swelling, which caused a stroke. Surgery saved Page’s life, but he incurred permanent neurological impairment as a result of his injury. He remained in a coma for four weeks. After his release from the hospital, Page required daily living assistance. In 2002, the Page family filed suit against the Kentucky Athletic Commission, the promoter, and the ringside doctor. The Pages were awarded a $1.2 million settlement in 2007.

FORMER CHAMPION AND A MAN OF FAITH

Although confined to a wheelchair and permanently paralyzed on his left side, Page recovered sufficiently to resume participation in life. Later in 2001, he married his girlfriend Patricia. The pair had originally dated during their high school years, before their lives took divergent directions. The relationship resumed in 2000, after Page returned to Louisville. Patricia was in the audience for the Crowe fight, and remained by Page’s side during his months of critical care and rehabilitation. Family and friends were there for Page, too. Dennis Page returned to Louisville to help with his brother’s living needs. Patricia’s daughters Teisha and Sierra were always on hand, and Page’s daughters from his first marriage, Alison and Alicia, flew in from Las Vegas to visit. Kelley Mays, indefatigably grateful for Page’s mentoring during their Baxter Street days, remained close to his old friend. Page’s many boxing connections were supportive: Oliver McCall called often; Larry Holmes, Tim Witherspoon, Scott LeDoux, and Renaldo Snipes lent their support as well.

World boxing champions are not normal people; the character traits that make them the best at their sport are reflected in other living areas well. This axiom was shown in Page’s courage and grace in the years following his injury. Page’s impairments did not prevent him from finding meaning and happiness in life. His disposition was generally sunny; he rarely expressed bitterness or self-pity. A devout Christian, Page often read the Bible, listened to gospel music, and watched sermons on television. Page humored himself by watching old sitcoms. He continued to follow boxing, rarely missing broadcasts of top bouts; among his favorite fighters were Manny Pacquiao, Bernard Hopkins, Zab Judah, and Paulie Malignaggi. Although Page’s short-term memory was impaired by his injury, his long-term memory remained quite good, and he loved to discuss music from past decades. Page liked to reminisce about his career achievements and peak experiences in boxing. He took particular satisfaction in reading fan mail: it meant a lot to Page to know that his performances gave people enjoyment, meaning, and excitement.

People grew through their relationship with Page during these years. The former champion’s character influenced others in positive ways. Driven to learn every aspect of the flawed medical and safety conditions she witnessed at the Crowe fight, Patricia became an expert witness at ringside physician conferences. The WBC made her an honorary ambassador for her activities in pursuit of boxing safety. Dennis established the Greg Page Foundation, a registered charity organized to assist people with disabilities.

Greg Page, the third best heavyweight produced by his generation, was a man of faith. The former champion had reasons for not being bitter. As he often said, “Be patient, God don’t like ugly.”