By Mike Casey: People love to tell funny stories about Mickey Walker. Lord knows, the boxing archives are bulging with them. I hope you will forgive me if I depart from well-worn tradition and simply praise Magnificent Mick for the truly fabulous fighter he was.

By Mike Casey: People love to tell funny stories about Mickey Walker. Lord knows, the boxing archives are bulging with them. I hope you will forgive me if I depart from well-worn tradition and simply praise Magnificent Mick for the truly fabulous fighter he was.

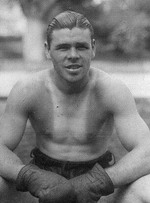

It seems that Mick, like his great rival and pal Harry Greb, never goes out of fashion. Walker’s rugged and mischievous face stares out gloriously from the old newspapers and magazines, forever young and vibrant, forever hip and cool. Pick any trendy word from any era and it fits the Toy Bulldog as snugly as a meaty bone clamped between the jaws.

He looked every inch a real fighting man, as did so many men of his great and quality-laden era. The rugged face was topped by a head of thick and tousled hair, while the powerful chest and muscled arms channelled down to a solid waist and sturdy, chunky legs..

Mickey Walker loved to fight, and there is the important difference with those who have it in their blood. Walker didn’t dread an upcoming battle or regard it as an inconvenience. He positively relished the assignment.

He was often too tough and willing for his own good, especially during his later forays into the heavyweight division. Yet he remained a vicious proposition right to the end, always winning more fights than he lost.

It is important to remember that many of Mick’s contemporaries were of the opinion that he was past his best by 1926, when he stepped out of his natural element of the welterweight division to take the middleweight championship on a debatable decision from the Georgia Deacon, Tiger Flowers. Mick had already waged many a ferocious and punishing battle by that time. Yet he ploughed on until 1935, defeating the hefty and classy likes of Johnny Risko, Bearcat Wright, Jimmy Maloney, King Levinsky and Paolino Uzcudun.

Walker conceded 42lbs to Bearcat Wright in winning a thrilling decision after being pounded, floored and nearly knocked out in the early going. The Bulldog was outweighed by 14 pounds in his astonishingly brave, losing stand against Max Schmeling. Against Jack Sharkey at Ebbetts Field in 1931, Mick was the lighter man by nearly 30lbs yet hacked out a gutsy 15-rounds draw.

How he raged against Sharkey! Coldly hammered for long periods and reeling in the fifteenth and final round from repeated rights to the jaw, Walker simply wouldn’t go under. He blazed back at Jack all night long and had the crowd in uproar in a fantastic ninth round. Mick snapped Sharkey’s head back in that session with a big right uppercut to the chin and followed up with a furious body attack. As Jack fired back, he walked into a cracking left hook to the jaw that made him hold.

Low blows cost Sharkey dearly and the draw decision was described by reporters of the time as one of the greatest upsets in boxing history. Mickey, covered in blood from a ripped eyebrow, was given a thunderous ovation.

Mickey Walker was a terrific body puncher who would often fire his punches in rapid blitzes. He could lead with a fast left hook, hurt and knock out opponents with either hand and possessed a hard and flashing right cross. His ability to punch damagingly at short range was exceptional. Much like Jack Dempsey, Bob Fitzsimmons, Jim Jeffries and Joe Gans, Walker learned the priceless value of the short and paralysing dig to the heart or stomach.

He loved to scrap, loved to live and possessed electrifying charisma. He was almost a lighter version of Dempsey in fighting savagery and box office allure.

Nat Fleischer wrote of Mickey: “He rated close to the top. A terrific hitter with an abundance of courage, he fought in every division from welterweight through heavyweight. Though far outweighed, he always gave a thrilling performance.

“He was a fabulous character, colourful, a powerful puncher; and while for a good portion of his career he was only an overstuffed welterweight, he made the grade in the three top divisions.”

Mick always saw himself as the little guy fighting giants, right from his days as a pugnacious young kid in his New Jersey neighbourhood of Keighry Head. Across from his favourite hangout of Cooper’s Corner was a big freight yard where hobos from all across America would stop off while waiting for the next ride out.

Walker inevitably got into fights with some of the toughs and quickly learned that he was most at home fighting bigger men. They were slower in their movement and made for much better targets than the smaller, slippery fellows.

Before boxing, Mickey Walker was going to be an architect. After boxing he became a very accomplished painter. But it was the fight game that snared him and enabled him to build and paint with the greatest effect.

Mick never did forget beating up on those guys in the freight yard. From the moment the inimitable Jack Kearns took up the reins as his manager, Walker was nagging him for fights against the heavyweights. But Mick’s blood-and-thunder affairs with the dreadnoughts were preceded by some glorious chapters in his natural domain. The welterweight and middleweight divisions were already gold-plated in their history and quality as boxing entered the Roaring Twenties. Then along came Mickey Walker. He was dubbed the Toy Bulldog by New York sports editor, Francis Albertini. And how the Bulldog could bite!

Historian Tracy Callis puts Mick’s fighting style and wonderful achievements into perspective: “Walker belongs in that class of fighter called iron men. He was tough, rugged and willing. His nickname of the Toy Bulldog was very appropriate. For like that breed of creature, he was short, stocky, sturdy, tenacious, determined and game. The size of his opponents did not matter. Fight meant fight against whomever stood before him, big or small.

“Mickey was a relentless warrior who could dish it out and take it too. In the heat of battle, he bobbed, squirmed, charged, weaved, ducked, slammed and smashed. Jack Sharkey described Mickey as ‘much tougher than Max Schmeling’.

“For the last half of his career, Walker fought at something like 164-173lbs. Only two or three times did he exceed this weight, the heaviest being 179lbs for one fight.

“During his career, if we use the latest BoxRec statistics as our yardstick, Mickey was outweighed by 10 or more pounds in 28 contests (rounding 9 1/2 or more to ten). Of these bouts, the difference was at least 15 pounds on seventeen occasions, and in 14 of these fights he was outweighed by 23 or more pounds.

“Against the huge foes (heavier by 23 or more pounds), Mickey’s record was 11-1-2 with six knockouts. Against men who were 15 or more pounds heavier, his record was 14-1-2 with seven KOs. When he was fighting men who were ten or more pounds heavier, Walker boasted a record of 22-2-2 with 13 knockouts. Two bouts were no-decisions in which Mickey won the newspaper verdicts.

“The list of fighters Mickey Walker beat includes Maxie Rosenbloom, Mike McTigue, Tiger Flowers, Paul Berlenbach, Jack Britton, Lew Tendler, King Levinsky, Paolino Uzcudun, Jimmy Maloney, Johnny Risko, Bearcat Wright, Jock Malone, Dave Shade, Leo Lomski, Arthur DeKuh and Paul Swiderski.

“In a poll of old-time boxing men conducted by John McCallum in 1974, Walker ranked as the number one all-time welterweight. Broadway Charley Rose ranked Mickey as the number three all-time middleweight. Nat Fleischer and Herb Goldman ranked him as the fourth greatest middleweight, as did the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO) in its poll of 2005.”

Jack Britton At The Garden

Jack Britton was a wonder and quite fittingly known as the Boxing Marvel. Counting the number of fights on Jack’s vast record required great concentration and a clear mind. He had fought them all and beaten most of them. The names of his illustrious opponents jumped off the page like jolting little boxing gloves on springs.

Britton was thirty-seven years of age and was the oldest living world champion when he defended his welterweight laurels against Mickey Walker at Madison Square Garden on November 1, 1922. But Jack was still a ring mechanic of sublime skill, toughness and endurance. He would eventually retire in his mid-forties with some 350 fights on his record, quite probably more, with only one knockout loss suffered as a novice.

Britton made a noble and brave stand against the hungry young Walker, but Jack’s know-how couldn’t offset his challenger’s youth, strength and power. It was an engrossing and exciting battle between the old king and the heir apparent, although the knowing and more cynical members of the crowd wondered if everything was on the level when the fighters first stepped into the ring. A certain hum went around the Garden following an announcement on behalf of the New York Commission and promoter Tex Rickard that all bets were off. Britton had been a 6 to 5 favourite the previous day, but Walker was the 3 to 5 choice by the time the preliminary bouts got under way.

Happily, there was nothing in the tough and gruelling battle between Mickey and Jack that offered so much as a hint of foul play. The Associated Press reported: “After 20 years in the ring, Britton, the crafty and ringwise master of defense, twice the holder of the crown that toppled last night, was a poor match for the aggressive Jersey man who displayed more than ordinary knowledge of the science of fisticuffs. Walker won all the way.”

Indeed, Jack might well have been knocked out in the later stages of the battle, had it not been for the hardness and resilience that had always been married to his innate skill. Most of the crowd had a fondness for the fading champion and didn’t want to see him take the ten count.

Mickey’s tiredness probably saved Jack from that fate. The challenger was still punching hard in the closing frames, but the effort of trying to trap and finish the old master had taken much of the steam from Walker’s blows. When Mickey’s forceful wallops rendered Britton glassy-eyed and uncertain, the champion’s great boxing brain would click back into gear and engineer a timely retreat.

Jack didn’t wait for the decision to be announced before congratulating Walker. “I wish you luck, boy,” was the dethroned champion’s sporting message. Mick told reporters that Britton was the gamest man he ever fought.

Mickey was a proud and successful welterweight champion, but was always hunting bigger game. His first crack at the middleweight championship proved a step too far too soon, but only because the reigning king was a certain Mr Harry Greb.

When Walker stepped up to challenge Harry for his crown on July 2, 1925, before a crowd of 50,000 at the Polo Grounds in New York, one of the greatest and most celebrated battles in middleweight history was contested. The two warriors waged a furious, fast-paced thriller, one of the best ever seen at the famous old venue, with Greb putting the seal on a memorable victory after a terrific rally in an unforgettable fourteenth round.

Harry suddenly nailed Mickey with a big right in that round that had the Toy Bulldog hurt and tottering. Walker backed into his own corner and swayed glassy-eyed as Greb unloaded punch after punch.

Then there followed a magical microcosm of what Mickey Walker was all about. He shook his head, water spraying from his dark hair, and cracked Harry on the chin with a big right. The heaving crowd went wild. As Damon Runyon reported, “A roar rolled up out of the bowl under Coogan’s Bluff that must have echoed over all Harlem and Washington Heights.”

The pace of the fight had been tremendous throughout and Walker closed strongly to win the final round. But it wasn’t enough. Greb had once again prevailed with his almost unique mix of ferocity, speed, guile and cleverness.

It was all too much for referee Eddie Purdy, who twice fell and injured a knee joint in trying to keep up with the whirling dervishes.

The sporting Walker forever credited Greb as being the greatest fighter he ever met.

Tiger Flowers and Ace Hudkins

The record-breaking crowd of 11,000 at the Coliseum in Chicago on December 3, 1926, couldn’t quite make up its mind. First the people booed the decision and then they cheered it. Many of those polled believed that Tiger Flowers had retained his middleweight championship by edging Mickey Walker by a 5-4-1 count in rounds. Others believed that Flowers had won by a greater margin.

But the decision of referee Barney Yanger went to Walker as blood ran down the Toy Bulldog’s chest from a badly gashed left eye he had sustained in the second round. Tiger grabbed Mick’s gloved fist and congratulated him, while 20 or more police officers climbed into the ring to protect the fighters from any crowd trouble.

Walker Miller, Flowers’ manager, had been concerned for some time beforehand that Tiger would be robbed if the fight went to a decision. Miller had demanded a forfeit from Walker’s manager, Jack Kearns, which guaranteed Flowers a return match within 90 days. Kearns further agreed that Flowers would be Mickey’s first challenger. Alas, Tiger Flowers would die a year later from complications following surgery.

Walker Miller was philosophical about Barney Yanger’s decision. “We had a good referee in there. He decided Walker won, so it must be so. However, Flowers was hit low two times and those punches took the steam out of him.”

It was a sensational fight that night in Chicago, with Mickey starting fast and finding immediate success with the first right hand punch he threw. Flowers fell to his haunches but was quickly on his feet again. Thereafter, the defending champion boxed wisely, preventing Mick from launching his damaging body attacks by moving well and fending off the Bulldog with raking long lefts and right crosses that flashed in from all angles.

Tiger was the 8 to 5 favourite and carrying a four-and-a-half-pond weight advantage at 159lbs. It seemed that he was now in gear and cleverly navigating his way to a fairly comfortable points victory.

But there was always a certain fragility about Flowers that denied him true and enduring greatness in the minds of many. He was in trouble again in the fourth round as Walker, in his increasing frustration, mounted a ferocious charge. Tiger bravely and intelligently continued to hold back the tide, but then the oncoming Walker nailed him in the ninth. A big right dipped Flowers’ knees and a similar punch sent him to the canvas seconds later.

Tiger showed great defensive skill in making Walker miss with his big shots as Mickey burrowed in and tried to finish the champion. Mick was constantly handicapped by blood running into his eyes and kept trying to clear his vision as he punched away. But the decision was his and so was the middleweight championship.

Mickey, for all the tough fights he had already had, thus opened another golden chapter in his career in which he seemed to gain a new lease of life. At twenty-five, he was a grizzled veteran by the standards of the day, yet he lost only one fight over the next three years as he narrowly failed in his bid to wrest the light heavyweight championship from the artful Tommy Loughran.

Mick was fortunate to get the decision over the vicious and uncompromising Ace Hudkins in a middleweight title defence at Comiskey Park in 1928, but how the Toy Bulldog made up for that in the return match!

Hudkins, the gloriously named Nebraska Wildcat, got his second chance at Wrigley Field in Los Angeles on October 29, 1929. A crowd of 25,000 saw Walker turn the clock back in spectacular fashion. Summoning all his old fire and brimstone, Mickey met Ace’s aggressive rushes with brilliantly timed counter fire. Over the course of ten rounds, Walker punched the teak-tough Hudkins virtually to a standstill with solid blows to the jaw and a consistently powerful body attack.

Mick had Ace in trouble from the outset with short and explosive lefts and rights to the jaw. The fast right to the jaw was always a speciality of Walker’s, and Hudkins was forced to hold on tight again in the sixth as Mickey crashed home his pet blow.

The fight was a great demonstration of the power and effectiveness of short-range punching, as Mick and Ace fought frequently at close quarters. Some of the greatest damage they did was with jolting little digs to the body and jaw. Walker, superbly fit and bronzed by the California sun, was always mixing up his shots, tagging the onrushing Hudkins with hooks and uppercuts.

Ace finished the punishing duel bleeding from a cut over his right eye and suffering from a split lip. Most neutral observers awarded Mickey eight of the ten rounds.

Mickey And The Greats

Regular readers will be aware of my admiration for that wonderful boxing writer of yesteryear, Robert Edgren. In general, Mr Edgren was fair and objective in his summations of fighters. He was also extremely knowledgeable and possessed a rare, instinctive feel for boxers and boxing technique.

He maintained to the end that no middleweight could compare to the astonishing Bob Fitzsimmons.

However, lest you should think that Edgren was obsessed with the fighters of his day, consider what he said as an older man when comparing Mickey Walker to past legends of that weight class. Edgren’s observations, published shortly after Mick’s storming victory over Ace Hudkins in 1929, might well surprise you as much as they did me.

“Barring Fitzsimmons, Walker looks just about as good as any of the middleweights. There is a glamour and a glory about past champions that makes them seem greater when they are gone from the ring than they seemed when we looked at them in action.

“Tommy Ryan was a great middleweight, but if you analyse his fights, they were no better than Walker’s. The same could be said of any of the rest – barring only Fitz.

“Harry Greb never knew much about boxing. He was a tireless windmill in action, swinging from bell to bell and able to sop up any amount of punching.

“Even the great Stanley Ketchel doesn’t figure so much better than Mickey if you look at facts and cut out the past glory. It took Ketchel 32 rounds to beat Joe Thomas, a clever middleweight, for the championship. Of course, in four fights he ruined Thomas completely, but I doubt that this tough egg Ace Hudkins would go through as many rounds with Mickey without being sent to the pugilistic dump.

“Jack Kearns always says that Mickey Walker is ‘another Joe Walcott’. He is like Walcott in build, although with bigger legs in proportion. Walcott was 5’ 1” tall when he was welter champion, and his neck and arms measured just 16 inches. He had the fighting equipment of a big heavyweight as far as strength was concerned.

“In the Hudkins fight, Walker showed amazingly good condition. I never saw him in better shape, even as welterweight champion. He was baked to a dark brown by the hot sun of the Ojai Valley and looked like a thick-set Jack Dempsey. When they fight for Kearns, they have to be aggressive.”

Training

Would Mickey Walker have been even greater if his love of fighting had been matched by a natural love of training?

No!! The latter discipline always made Mick bristle with irritation and restlessness. But in common with other like-minded souls, there was a deception to his lack of enthusiasm that was frequently misunderstood.

Damon Runyon often wrote amusingly of Walker’s slothful, half-hearted sparring sessions. Casual visitors to the gym would gawp in disbelief as they watched the famous killer of the ring engaging in a series of quaint and inoffensive waltzes with his partners.

Mickey was a wild horse and a free spirit who simply had to do it his way, the only way that worked for him. That meant walking the tightrope and maintaining a precarious balance between the rigours of training and the pleasures of wine, women and song. Ketchel, Greb, Monzon and Duran were from a similar mould. To them, there was no challenge to punching a bag or running for miles. It bored them. But each was sensible enough to know that the monotonous groundwork was a necessity. They simply tilted the conventional plane and fashioned their own schedules.

Here is how Mickey Walker saw it when he spoke to writer Peter Heller in the early seventies: “The most important thing for young fellows now who are thinking about boxing is to be in shape. Don’t neglect that. Get in training. You need that, and your training consists of roadwork and boxing in the gymnasium. These amateur fighters of today are making a big mistake because they don’t do enough hard work. They get in the gym and all they do is box three rounds, punch the bag maybe two rounds, and maybe do a little exercise and that’s their day’s training. You need more work than that.

“What you should do in the gym is box about four three-minute rounds every day when you’re in there training. When you’re in the ring it gives you endurance, and you need endurance. Punching the heavy bags, that’s good, but punch them more than a minute. Punch them three minutes and you’ll find that a big difference. In our day, we had real professional trainers who knew all that. I followed their advice. In the morning, you’d be up and you’d do from five to ten miles roadwork daily. You run half of that and walk the other half. That’s in the morning.

“Then in the afternoon, if you’re fighting a 10-round fight, you’d box a fight in the gymnasium, eight or ten rounds, punching the bags, and you’d do stomach exercises to harden you up. You have to be hardened from toes to head.

“Today, the boys in there, they look like they’re only training for speed. Well, you need more than speed. You need endurance, you need something in your body that you can take a punch, and that’s what they’ve got to train for.

“In the modern times, everything is fast, speedy. But there’s some things in life we can’t do that fast or speedy. Only one thing about fighting – you need to be able to punch, you need to be able to take a punch, and if you go too fast in your training you miss a lot.”

What made Mickey Walker different from the norm was that he couldn’t do such things within the boundary of a set timetable. For Mick, the difference between day and night needed to be blurred. Time and timepieces were of scant importance to him.

Manager Jack Kearns made this discovery when he got it into his head that a more regimented training regime would work wonders for Walker and push him to greater heights. Jack got his great idea at Madame Bey’s camp while Mickey was preparing for a fight with King Levinsky. Trainer Teddy Hayes, much more knowing in such matters, was out west on other business and blissfully unaware of this potentially fatal change to Walker’s civilised routine. Kearns’ fanciful notion was at once doomed to failure. It gave Mick the collywobbles and upset his entire system.

Jack wanted him to cut down on the booze, eschew sweet and fatty foods and go for long runs at the crack of dawn. The great plan quickly bombed. The clincher, the one rule that gave Walker the shudders more than any other, was that he had to go to bed early.

As hard as he tried, Mick simply couldn’t persist with what he regarded as the sacrilegious act of retiring to his bed on the same day he got out of it.

Mike Casey is a boxing journalist and historian. He is a member of the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO), an auxiliary member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and founder and editor of the Grand Slam Premium Boxing Service for historians and fans (www.grandslampage.net).