15.07.08 – By Mike Casey: He jabbed with laser-like accuracy, he slipped and blocked punches, he double-feinted all night long in a sublime exhibition of masterful boxing. For forty-five minutes of near technical perfection, Harold Johnson mesmerised the more than capable Doug Jones on a May night in Philadelphia in 1962.

15.07.08 – By Mike Casey: He jabbed with laser-like accuracy, he slipped and blocked punches, he double-feinted all night long in a sublime exhibition of masterful boxing. For forty-five minutes of near technical perfection, Harold Johnson mesmerised the more than capable Doug Jones on a May night in Philadelphia in 1962.

Like a rare diamond that had been kept shut away in a vault, Johnson finally stepped out and sparkled as the master of all he surveyed among boxing’s 175-pounders. How great was he on that magical night in the City of Brotherly Love? Well, Doug Jones would go on to scare the life out of young Cassius Clay just ten months later. Against Johnson, Doug could barely hit the target, never mind hit it with anything worthwhile.

Jones was no mug. He was a tough, hard-hitting fighter who compiled a solid and honourable world class career. Against Johnson, however, Doug was a bewildered pupil against a master..

Entranced ringsider Lew Eskin wrote: “Harold Johnson may not be the best fighter in the world, but there were few among the 5,000 plus who sat in on his fight with Doug Jones in the Philadelphia Arena who could argue the point, and that included Jones.

“The thirty-four year old Johnson, a veteran of seventeen years in the professional ranks, gave a masterful performance as he handed out a lesson in the art of boxing.

“From the outset Johnson’s left was a thing of beauty as he stabbed his foe off balance in a continuing pattern of motion. Doug, with only twenty fights behind him, could not figure out a defense for Harold’s left.

“Round after round went by along the same lines. Jones would try to open up Johnson so that he could land his right, but to no avail. When he was ready to punch, Harold would shift, jab and be gone.

“Jones tried to double feint Johnson, but ended up off balance as the veteran double feinted him into knots. Doug had the edge in reach, but was unable to make use of it as Harold would slide his head out of the way of jabs and counter with his own, or as Doug was moving forward, shift and nail him with a right hand lead.”

Adage

Contrary to the old adage, people do sometimes remember the guy who finished second. But that is scant consolation to those luckless souls who never quite achieve the recognition they strive for. What must it feel like to be a champion, win every trophy in the case and still carry the stigma of being second best because someone out there is even better than you? Ask Esteban DeJesus, who just happened to share the same pocket of time with Roberto Duran. Ask Howard Winstone, who got Vicente Saldivar as his swinging sixties companion. Rodrigo Valdez, the brilliant Colombian middleweight, had to put up with a fellow called Carlos Monzon.

In a far gentler domain, a long time ago, I became acquainted with the feeling of trying to overtake a natural talent. Excelling in English and History, I was kept out of the number one spot in both classes by an earnest fellow who once told his careers officer, in all deadly seriousness, that he wanted to be Prime Minister of Great Britain. I whipped everyone at English and History, but I never could beat the would-be Prime Minister.

Now imagine, if you will, a similar scenario. A marvellous ring mechanic compiles a glittering record against some of the finest fighters in the business. He wins the world championship and is acknowledged by his peers and critics as a master of his trade. Yet throughout his career, he is consistently overshadowed by a fighter of even greater ability and stature.

Many fine ringmen have fallen into this category, yet the man who prompted these thoughts was former light heavyweight champion, Harold Johnson.

During a recent sort-out of the hundreds of boxing magazines that make my study resemble a besieged fortress, I came across a copy of Johnson’s record and this inevitably led to my seeking out original reports of his fights. Most accounts were glowing tributes to Harold’s superb skill and general boxing prowess, some devoid of even the slightest criticism.

Yet who talks about Johnson now? Here was a man who laboured for years to win the biggest prize in his class. He never gave up the chase and he toiled in an era of ferocious competition when a dozen wins wouldn’t get you a shot at the world crown. How many realise that he wound up in a gloomy old people’s home in his native Philadelphia with a rapidly fading memory?

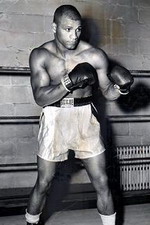

As a young fighter working his way up the ranks, Harold Johnson was certainly a sight to behold. He was a magnificent physical specimen throughout his career, a natural in the way of Max Baer. Harold was proud of his fitness. Several years ago, he told writer Tris Dixon: “I was very good in training. A lot of fighters told me they wish they could have trained like me, because I was always training.

“I was always running in the morning at about 6.30, not too early, not too late. I’d run in the rain and the snow because I wanted to be in good shape to fight. I used to jump rope and loved the speed bag. A lot of guys wished they could hit the speed bag like I could, too. I guess I had a little rhythm. I’d have music on when I hit it and punch to the rhythm. I always took it seriously – everything I did in training I’d take seriously.”

Johnson couldn’t abide alcohol and was quick to point out that weights played no part in carving his outstanding muscular definition. “The only weights I lifted were dumbbells for shadow boxing to put power in my punches. I was told I could hurt myself lifting weights, so I didn’t. I didn’t want to get injured.

“It’s no good for fighters – it makes you slow, muscles you up. They might give you power, but your opponent will see your punches coming. What’s the point in having power if you can’t hit nobody? People were sure I lifted weights, but I never.”

Heyday

Even in his heyday, Harold Johnson’s name was never one to fire the imagination of the greater boxing public. He was never a fashionable or exciting fighter, but rather one of that rare breed whose gifts are only appreciated by the connoisseurs. More significantly, perhaps, he was misfortunate in being a contemporary of the one man he couldn’t beat when it counted the most: Archie Moore.

The record book tells us that Johnson outpointed Moore over ten rounds at Milwaukee in December 1951, but it was Archie who dominated their five-fight series by a score of four to one. The Old Mongoose underlined his mastery of Johnson in audacious fashion in their final meeting in New York in 1954. Challenging for Moore’s light heavyweight crown, Harold scored a tenth round knockdown and seemed assured of a points victory with only two rounds to go. But his hopes were brutally dashed in the fourteenth as Moore launched a dramatic attack to floor Johnson and force a stoppage.

Moore always seemed to strike at the wrong moment in Johnson’s life. It was Archie who had inflicted Harold’s first professional defeat in 1949. The die was cast. There was a division of class between the two men, however thin, and it was Johnson who ran second. If Johnson ever felt that fate had singled him out as a nearly man, he made an admirable job of disguising his frustration. He was a model professional who took his lumps with dignity and never stopped pursuing his dream of becoming world champion. By the time of his eventual coronation in 1961, he had been a professional for fifteen years and his record sparkled with the names of famous fighters.

The son of a good class heavyweight, Phil Johnson, Harold turned professional in 1946 and won his first twenty-four fights before dropping his first decision to Moore in Philadelphia in 1949. Among Johnson’s victims that year were the tough Chilean, Arturo Godoy, who twice challenged Joe Louis for the heavyweight title, Bert Lytell and Jimmy Bivins, who had been caretaker champion during the Brown Bomber’s stint in the army.

In February 1950, the still young and relatively inexperienced Johnson stepped out of his class when he crossed gloves with the seemingly ageless Jersey Joe Walcott, who would proceed to win the heavyweight championship a year later at the age of thirty-seven. Walcott knocked out Johnson in three rounds at Philadelphia in an odd twist of fate. Jersey Joe had kayoed Harold’s father in the same city and in similar time some fourteen years before.

Harold took some time to recover from the defeat, and it was December of that year before he came back to knock out Harry Daniells in two rounds. Johnson scored a further four victories before the haunting figure of Archie Moore stepped out of the shadows to torment him again. Between September 1951 and July 1952, the two men clashed three times, with Johnson’s lone success in Milwaukee being outweighed by two defeats.

Yet it would be wrong to suggest that Moore was the only obstacle in Johnson’s path. Top class fighters were richly abundant in every weight class at that time and generally had only one undisputed champion to aim at. Even the light heavyweight sector, historically boxing’s most maligned division, featured a host of tough and talented ringmen. The swarthy and skilful Joey Maxim was the champion, and among the other outstanding contenders were Harry Matthews, Wesbury Bascom, Bob Satterfield, Bob Murphy, Yolande Pompey, Dan Bucceroni and Danny Nardico.

Progress was hard even for a fighter of Johnson’s calibre, yet it was a measure of Harold’s ability that he was also able to step up a weight class and defeat ranking heavyweights. Within two months of losing his third fight to Moore in Toledo, Johnson decisioned Clarence Henry, rated among the top ten heavies at that time, and then split a pair of decisions with that dynamite puncher, Bob Satterfield. Harold rounded off his 1952 campaign with a points victory over Nino Vales in Brooklyn.

While it is possible for a young American boxer of today to go through a whole career within a tight geographical circle, fighters of Johnson’s era constantly criss-crossed the country to get work. In 1953, Harold fought in New York, Toledo, Miami Beach, Philadelphia, Milwaukee and Hershey, posting victories over Jimmy Slade, Toxie Hall and Ezzard Charles.

When Johnson finally challenged Moore for the championship the following year, it seemed Harold was on the verge of dispersing the black cloud that had hovered over him for so long. The manner of his defeat was almost too cruel to be true and his chance of levelling the score with Archie was gone forever. Fate kept the two men apart thereafter, and while Moore set his sights on heavyweight champion Rocky Marciano, Johnson’s career nosedived. Two months after the Moore setback, Harold was knocked out in two rounds by Oakland Billy Smith and engaged in only five fights over the next two years.

He was judged the villain of the piece in a bizarre meeting with former victim Julio Mederos in May 1955, in which Johnson collapsed mysteriously in the second round and later claimed he had eaten a poisoned orange. He was subsequently fined for a suspected dive and it was nearly two years before he got his next fight, when he outscored Bert Whitehurst in Portland, Maine.

Making

Perhaps the Mederos incident was the making of Johnson as a fighter, because it was eight years before he was beaten again, even though he competed infrequently. He fought only twice in 1959 and just once in 1960, but in 1961 the years of experience shone through gloriously as the hard old campaigner won himself a share of the light heavyweight championship.

The former National Boxing Association (now the WBA) stripped Archie Moore of the championship for his failure to defend, and Johnson was matched with Jesse Bowdry for the vacant title at Miami Beach. Harold was magnificent in outclassing Bowdry, stopping his man in the ninth round after a faultless exhibition of box-fighting.

Yet the constant presence of Archie Moore continued to haunt Harold. “I won the NBA title,” he said, after defeating Bowdry, “but I won’t feel like a real champion until I beat the old man, Archie Moore.” That day would never dawn for Johnson, but he did the next best thing by decisively beating the best challengers the division could offer.

Indeed, 1961 and 1962 were arguably Harold’s finest years as a fighter. In his first title defence, he had the calm and relaxed look of a man taking a walk in the park as, almost effortlessly, he knocked out his fellow Philadelphian Von Clay in two rounds.

With each succeeding fight, Johnson improved irresistibly like vintage wine. When he outpointed top ranking heavyweight Eddie Machen in a non-title match in July 1961, there were those who were so impressed by Harold’s skills that they accorded him an excellent chance of beating the mighty Sonny Liston. Johnson’s next title defence against another grand veteran, Eddie Cotton, was a somewhat poignant affair for those who truly feel for their fighters.

Cotton was an excellent ring technician, who had also laboured long and hard to earn his title chance. But while Johnson had fought in the shadow of one legend, Cotton had toiled in the shadow of two. Eddie had the misfortune of being the third man in the triumvirate of Moore, Johnson and Cotton, a man who could have been king but for his two great contemporaries.

When Eddie finally got his chance in his hometown of Seattle, he challenged Johnson spiritedly but could not beat him. Harold paced himself beautifully, closing the fight strongly to win a unanimous decision. It was to old Eddie’s credit that, all of five years later at the age of thirty-nine, he would challenge for the title again and convince thousands that he had done enough to dethrone Jose Torres.

Superb

Harold Johnson had truly come into his own and was rightly hailed as a superb, thoroughbred champion. In 1962 he was again unstoppable as he saw off two of the finest contenders of the decade in Doug Jones and Gustav Scholz. The Jones triumph was one to savour for Harold, for at last he was given universal recognition as world champion. Johnson then travelled to Berlin to face Scholz, scoring another emphatic points win. The defeat was one of only two suffered by Scholz in 96 professional engagements.

It seemed that Johnson would reign interminably, but in June 1963 the master boxer caught a tartar when he was toppled from his throne in a major upset. He pitted his crown against Willie Pastrano in Las Vegas, in what seemed a fairly safe defence. Pastrano was an experienced and skilful campaigner, but a bon viveur and poor trainer whose recent form had been erratic. Willie had lost, drawn and won in three successive fights with fellow contender, Wayne Thornton, and was third substitute for the Johnson fight.

But the slick stylist from New Orleans frustrated Harold with speed, guile and a flicking jab to shock the fight fraternity by winning a close and disputed split decision. Many observers believed that Johnson had won the bout comfortably and the verdict caused a storm of controversy, yet Harold took his defeat with supreme grace and sportsmanship.

It was as if he had become quietly resigned to the fact that fate was never going to hand him any special favours. Discussing the fight in a 1970 interview, Pastrano said of Johnson: “Harold took it like a man, even though it was close. He didn’t squawk, he didn’t say boo. His manager did a lot of screaming. Harold just took his hand wraps off. I told him, ‘You’re a man, baby’. He’s still a fighter’s fighter.”

Johnson was thirty-five by that time, and most thirty-five year old ex-champions were ready for an easier life in those more competitive days. Yet Harold plodded on for a further eight years, campaigning only occasionally, yet still showing flashes of his old brilliance in beating some quality fighters.

He fought only once in 1964, knocking out the tough Hank Casey in eight rounds. Johnson was inactive in 1965, 1969 and 1970, yet kept resurfacing to defeat the stellar likes of Herschel Jacobs, Eddie (Bossman) Jones and European champion, Lothar Stengel. Harold was like a ghost from the past during that final phase in his career, an old maestro who kept coming back to show the Young Turks how it was done.

Time finally ran out for the grand old professional in 1971, when he attempted to shake off the rust of a two-year layoff in a return fight with Herschel Jacobs. Even at forty-three, Harold still possessed much of his old magic, but after winning the first two rounds, he was stopped on a cut eye in the third. He never fought again and faded quietly from the scene, but he should never be forgotten.

We live in an age of megastars and megabucks, where everything is larger than life and frequently pumped up out of all proportion. The past seems to recede and grow insignificant with ever greater rapidity, like an old black and white film. Past champions are all too quickly dismissed as old hat by those who can’t be bothered to get out their shovels and dig.

I only hope that the passing years don’t behave so cruelly to Harold Johnson. In an era when Philadelphia was renowned for its fistic scientists, Harold earned his degree.

• Mike Casey is a boxing journalist and historian. He is a member of the International Boxing Research Organization (IBRO), an auxiliary member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and founder and editor of the Grand Slam Premium Boxing Service for historians and fans (www.grandslampage.net).