Bobby Chacon on right) 23.12.07 – By Ted Sares: May 24, 1974 was the date they first met in the ring. It was at the smoky Sports Arena in Los Angeles and, as announcer Jimmy Lennon Senior exclaimed, it was the long awaited meeting of two of the West Coast’s best fighters. These two warriors fought like, well warriors, but in the end “The Schoolboy,” Bobby Chacon, took out Danny “Little Red” Lopez with a savage onslaught that ended at the 48 second mark of the ninth stanza. The final punches landed with full leverage rendering Lopez helpless and giving the referee no alternative but to stop the fight.

Bobby Chacon on right) 23.12.07 – By Ted Sares: May 24, 1974 was the date they first met in the ring. It was at the smoky Sports Arena in Los Angeles and, as announcer Jimmy Lennon Senior exclaimed, it was the long awaited meeting of two of the West Coast’s best fighters. These two warriors fought like, well warriors, but in the end “The Schoolboy,” Bobby Chacon, took out Danny “Little Red” Lopez with a savage onslaught that ended at the 48 second mark of the ninth stanza. The final punches landed with full leverage rendering Lopez helpless and giving the referee no alternative but to stop the fight.

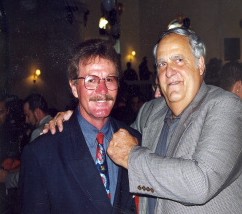

Several decades later, they would meet again at the World Boxing Hall of Fame in California and when “The Schoolboy,” dressed handsomely in a blue grey suit, saw” Little Red,” he yelled out in an almost child-like voice “Danny” and ran across the hall to hug him. Those who witnessed this emotional reunion will never forget it; it was powerful stuff.

What had happened to these two West Coast warriors leading up to this reunion is the stuff movies are made of, but in Bobby’s case the story is so melodramatic, no one is likely to buy it.

In the end, Chacon would be World Featherweight Champion from 1974 – 75 and World Super Featherweight Champion from 1982 – 84. Lopez would be the World Featherweight Champion from1976-80. The excitement they provided in the process was more than any boxing fan could reasonably hope for.

Bobby

I had it all, and I threw it all away

—Bobby Chacon

Bobby Chacon, a Hispanic-American, was born on November 18, 1951 in North Hollywood, CA.

He went from shiftless, gang-banging hood to the very top, but he had trouble staying there. He was called “Schoolboy,” more for his youthful appearance than for attending classes at California State University at Northridge. After a great amateur career, he turned pro on April 17, 1972, and ran up 26 wins (23 by Kayo) in his first 27 bouts. Along the way, he beat Tury Pineda (KO 5), Irish Frankie Crawford (W 10), Chucho Castillo (KO 10), and the aforementioned “Little Ped” Lopez. He stopped Venezuela’s Alfredo Marcano in nine rounds to win the WBC featherweight title on September 7, 1974, and followed with an easy (KO 2) defense against Jesus “Papelero” Estrada

But things began to unravel. Firing his manager manager-trainer Joe Ponce soon after becoming champion, he showed up in 1975 for a title defense against the great Ruben Olivares overweight, under-trained, and in poor shape. Things you just don’t do if you are fighting the likes of Olivares who floored Chacon twice in the second round before referee Larry Rozadilla waved off the action and made Bobby an ex-champ. He would defeat Olivares when he scored a 10-round win in their third match in 1977.

Embarrassed and depressed, he quietly relocated to Northern California. Meanwhile, Valorie, his beautiful Chinese-Irish wife, pleaded with him to quit fighting. Tragically, her suicide in 1982 was blamed in part on his decision to continue fighting.

While battling personal demons and habits, he continued his quest for another shot at the title he once had taken for granted. He managed to keep winning, but he was not the Chacon of old. His first bid to regain the title ended in a bloody technical draw with Bazooka Limon in 1979. He then lost to the great Alexis Arguello. Cornelius Boza-Edwards spoiled his third challenge for a title in 1981.

But then miracles of miracles occurred as he outlasted bitter rival Limon to take the WBC super featherweight title before a national TV audience in the 1982 Ring Magazine Fight of the Year. He also was named Ring Magazine’s Comeback Fighter of the Year in 1982. Neither man knew how to quit in the boxing ring. Quite simply,this was one of the great fights of all time, as both men stepped to the brink.

As fellow writer Mike Casey writes in his brilliant “Helter Skelter” (January 29, 2006): “…within the confines of its own little arena of relevance, it was a fight and an experience that pumped fresh blood to the hearts of tired people who begin to believe that the next day will be the same as the last. It was a fight that lasted for forty-five minutes yet which seemed to flash past in half that time. It had to go the full fifteen rounds, because Chacon and Limon were men who lived for such marathon tests of endurance.”

Five months later, he came from behind in explosive fashion to beat Boza-Edwards in boxing’s 1983 Fight of the Year. Two successive fights; two successive Fights of the Year. After losing to a heavier Ray “Boom-Boom” Mancini in 1984, Bobby ran off seven straight wins against very good opposition before retiring in 1988 with a reputation of being one of the most exciting fighters in boxing. A few years later, one of Bobby’s sons was killed in a gang-related shooting adding to the considerable emotional turmoil he had already gone through. Unfortunately, he had suffered considerable physical damage as well.

Today, he suffers from the dreaded dementia pugilistica (boxer’s syndrome) and his fortune has vanished, but his sense of humor remains intact as does his trademark smile. There are times he can’t recall people he’s known all of his life. While monitored by a nurse employed by the state of California, he continues to receive the affection of fans wherever he goes.

He won 59 of 67 fights and scored 47 knockouts. He holds victories over seven men who held a world title: Olivares, Castillo, Lopez, Marcano, Limon, Edwards and Frias. He was inducted into both the World Boxing Hall of Fame and the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Bobby’s life story probably will never be made into a movie; hell, who would believe it?

Danny

It’s great to know that I left an impression –Danny Lopez

Danny Lopez and the author

Danny Lopez and the author

Danny, an Irish/Mexican/American Indian, was born on July 6, 1952. He had been moved from one foster home to another, and coming off a Ute Indian Reservation in Utah, he finally found a home in Southern California.

Little Red was “Mr. Excitement;” he was never in a dull fight and was most dangerous if he had been decked–which was often. Soft-spoken and humble, he was ferocious and unrelenting once the bell rang. In an era in which fights were regularly seen free on non-cable television, he was one of the greatest of the television fighters and his name guaranteed big ratings. Danny was a volume puncher who worked to set up his knockout blow which he could deliver with either hand. His fights often turned into melodramas in which he overcame knock-downs, severe punishment, and adversity to score sudden and spectacular knockouts. In this regard, he was like Matthew Saad Muhammad. He would get off the canvas and roar back. Turning predator, he would hunt down and take out his opponent in savage fashion. He was heavy-handed and if he connected flush, it usually spelled the end for his opponent.

As Lee Groves states in an article on Everlast.com, “Little Red.… was boxing’s

ultimate thrill ride, a television fighter’s television fighter whose bouts stirred the

passions of red-blooded boxing fans everywhere…”

Managed by Hall of Famer Howie Steindler and Benny Georgino, he was an incredible power puncher with either hand, and bombed his first 23 foes into submission. After a temporary and savage derailment at the hands of the aforementioned Schoolboy and a collision-in-the-eye loss to Shig Fukuyama, he resumed his warpath ways.

Against the equally popular Chacon, 23-1 coming in, and before over 16, 00 fans at

the Sports Arena in LA, “Little Red,” 23-0 at the time, would lose his first fight. He had won his first 21 fights in a row by knockout. Like Chacon, he would often take a beating in order to give one back. The fast, equally dangerous and more skilled Chacon, who was always tough inside, prevailed on this night. Lopez had lost for the first time in 24 fights. He was just 21 and had yet to reach maturity. He was under the featherweight limit at 123 1/2lbs and knew the problem. He needed to come in at a heavier weight; he needed to be stronger. Lopez improved and became a World Champion just two years later.

He kayoed “Chucho” Castillo, Ruben Olivares, Raul Cruz, Sean O’Grady, Famoso Gomez, and Art Hafey en route to the featherweight title which he won by beating David “Poison” Kotey in the latter’s home town of Accra, Ghana in front of over 100,000 hostile fans. He defended the title successfully eight times against outstanding challengers. In 1979, he too fought in a Ring Magazine Fight of the Year against Mike Ayala winning by a dramatic 15th round knockout.

Finally, he lost his championship to the legendary Salvador Sanchez. After failing to regain it from Sanchez, he retired with a 42–6 record and a KO percentage of 81%, extremely impressive given the high level of his opposition. Like Chacon, he left boxing with a reputation of being one of the most exciting fighters to toil in the square circle.

Boxing provided the financial wherewithal for Danny to buy a home in which to raise his family. Recently united with his brother, former welterweight contender Ernie “Indian Red” Lopez, he now works construction in California and seems quite content with his life. He has been the object of various dedications and, like “The Schoolboy,” receives the affection and adulation of fans wherever he goes.

Lopez was inducted into the World Boxing Hall of Fame at age 35, the youngest man ever elected. But inexplicitly, he is not in the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

One thing is certain; both were always the perennial crowd favorites, and their respective legacies are forever secure with aficionados.

Ted Sares is a boxing writer and historian. He is the author of the recently published Boxing is my Sanctuary.