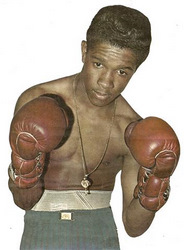

By Raul Porto – Today nobody would dare to deny that Bernardo Caraballo was during his time as an active boxer Colombia’s most commented sportsman, not only by the people but also by the media. The fact that he’s one of the finest boxers our country has ever produced can’t be ignored, either. It’s been said, rightly, that Bernardo Caraballo divided the history of Colombian boxing in two and that he gave to it the prestige it has today around the world. It was Bernardo Caraballo the man who opened international doors by leaving an indelible mark that few years later reached its peak with the establishment of “Pambelé,” “Rocky” Valdés, the Cardona brothers, Miguel “Happy” Lora, Fidel Bassa and most recently kids such as Yonnhy Pérez, Juan Urango, César Canchila and Ricardo Torres.

By Raul Porto – Today nobody would dare to deny that Bernardo Caraballo was during his time as an active boxer Colombia’s most commented sportsman, not only by the people but also by the media. The fact that he’s one of the finest boxers our country has ever produced can’t be ignored, either. It’s been said, rightly, that Bernardo Caraballo divided the history of Colombian boxing in two and that he gave to it the prestige it has today around the world. It was Bernardo Caraballo the man who opened international doors by leaving an indelible mark that few years later reached its peak with the establishment of “Pambelé,” “Rocky” Valdés, the Cardona brothers, Miguel “Happy” Lora, Fidel Bassa and most recently kids such as Yonnhy Pérez, Juan Urango, César Canchila and Ricardo Torres.

First steps

“I recall as if it was today when my brother Humberto took me to the boxing gym located in the Manga neighborhood, where he trained. I was 17 and I was a street-fighter in Chambacú, where I lived. I used to fight every day at Parque del Centenario and Camellón de los Mártires, places where I worked polishing shoes to make a living, you know. The first thing I did upon arriving into the gym was hitting the bag, as everybody did.. Mr. Julio Carvajal, a Chilean, was the trainer in charge. He gave me a trunk and a pair of boots, so I could replace the sandals I had. My first fight came after a week of training. It was against Daniel Ortiz at Turbaco’s theater. Mr. Galo Ramos took me to the scenario and I won by decision. The paid me $10… What a memory, huh!”

We are at the entrance of his house located on La Paz Street at the Torices legendary neighborhood in Cartagena de Indias, Colombia. A life-long desire of mine is being fulfilled today: to be in front of the idol, listening to his remembrances. I caught him watching soccer on TV. It’s bizarre. “Hey man, there is nothing else to watch. What do you want me to do?” –He asks.

Bernardo Caraballo was born in the new year’s eve of 1942 in Bocachica, a seaside community located in the Tierrabomba Island, where he lived until eight. Then he moved to Cartagena along with his father, landing in the poor, black neighborhood of Chambacú. As a boy, getting some sort of education wasn’t in his plans. Reading, writing and counting wasn’t meant for him, so in order to make a living he started to sell ice creams and brooms.

Medalist and Professional

“I loved boxing. It attracted me and I didn’t miss the fights of Raúl Macías that were shown at Variedades Theater. I became a local champion after six months practicing along with Mr. Carvajal. In the same year of 1959 I became paperweight national champion here in Cartagena and the following year I became flyweight champion at the VIII National Games. Let me tell you an anecdote: It happened that they matched me against Juan Herrera to see who was going to represent Cartagena at the paperweight division. I lost and they decided to match us again and this time I won. Then they took both of us, he as a paperweight and me as a flyweight. He and I claimed gold.” The VIII National Games helped him to launch his career. There he showed his qualities and people started to talk about the “Black Man” from Bocachica.

It’s the beginning of 1961. Caraballo officially makes his pro debut fighting Carlos Angulo, but as he himself confesses, his first professional fight was in mid 1960 in Barranquilla when he supplanted a brother of “Pinky Boy” Camargo in the same card where Mario Rossito faced Venezuelan César Orta, better known as “The Black Ram.” “That day I fought José González, the one who was called “Wooden Leg”. Camilo Morales came from Barranquilla looking for me in order to replace the other guy. ‘Focha’ Hernández was the promoter and he signed me to fight for $270, but paid $240 and still owes me $30 plus the interest… that a lot of money! Later I fought in the VIII National Games and one of the delegates tried to prove I was already a professional, but he couldn’t.”

The King of the Ropes

Perhaps the most important characteristic Caraballo showed as a boxer was his unmistakable style. It was something so natural that made boxing more than an art. From the beginning he was a stylist and he says nobody taught him that. The pair of legs he exhibited to walk the ring made of him a dancer, his velocity to escape from the ropes, his incredible sight, as well as the coordination with which he moved hips and head to avoid getting hit and the speed to release lethal combination of hooks and straights, made of this man a nightmare to any rival and a joy to the crowd who shook the arena to its very foundation. That’s why he was an idol!

“You know what? Nobody taught me that! Everything I did, I invented it. I never considered myself a puncher. I knocked people out because I threw a lot of combinations. It’s true I was very fast, that’s why people in Chambacú called me “The Deer” because I was speedy. Let me remind you that my first trainer as a pro was ‘Chico de Hierro’ and my promoter was ‘Moralito’, with whom I had a verbal agreement.”

The Master Punch

“From the very beginning of my boxing career journalist Filemón Cañate wanted to call me ‘Kid Centenary’, but I didn’t agree with that. I told him ‘respect me, don’t give me such sissy nickname’, find something different.” We’re at the end of 1961, Caraballo had married his neighbor Zunilda Contreras, a woman who later will teach him how to read, write and count “because I didn’t know anything,” Bernardo comments.

On December 2, 1961 at “Once de Noviembre” baseball stadium, the first world-ranked boxer fights in Colombia. It’s Venezuelan Ramoncito Arias, ranked number 2 in the flyweight division. He fights Caraballo in a bout that, on paper, seems to be uneven. But the contender looks slow, sloppy, way too far from what he has shown in the past. He underestimates the Colombian, who takes the opportunity to show all his resources and talents. That night a star was born, while the other one died out. The Arias-Caraballo bout was commented on both sides of the border, especially in Venezuela, where the media, in an effort to explain Arias’ poor performance, said he had been contracted to lose.

“For that fight I was paid $100. Later we had a rematch in Venezuela, where things were even easier for me. I got $5,000 bucks. My trainer ‘Chico de Hierro’ couldn’t go with me, so I went with Cuban Sócrates Cruz, a man to whom I owe a lot. He wasn’t only a trainer. He was my counselor, my friend. He taught me discipline.” The rematch in Venezuela was a sold-out event where Caraballo outboxed and outclassed Ramoncito Arias. As a consequence of that victory, in July 1962, Caraballo appears on the NBA’s ranking as number 9 in the flyweight division, thus becoming Colombia’s first world-ranked boxer ever. That was a national event! “Let me confess something: That wasn’t important for me at all because I didn’t know what it meant. Later my manager explained what it was.” This was the official ranking for the 112 pounds:

Flyweight: Champion: PONE KINGPETCH (Thailand)

1.-Sadao Yaoita (Japan); 2.-Pascual Pérez (Argentina); 3.-Ramón Arias (Venezuela); 4.-Salvatore Burruni (Italy); 5.-Horacio Acavallo (Argentina); 6.-Mimún Ben Alí (Spain); 7.-Kye Noguchi (Japan); 8.-Ray Pérez; 9.-Bernardo Caraballo (Colombia); 10.-Chucho Hernández (Mexico).

Career of an Idol

After his second victory over Arias, he outworks Panamanian Pedro Carvajal and Costa Rican Lolo Messén. Wins the flyweight national belt by defeating Jaime Caro, destroys American Ronnie De Cost and dangerous Spaniard Mimún Ben Alí, defeats Venezuelan Armando Blanco, former world champion Pascual Pérez of Argentina and Italian Piero Rollo. Then he moves up to the bantamweight division, soon becoming national champion by castigating Miguel Cabezas. Later he’s taken to Manila, Philippines, where he destroys Marcel Juban and Chartchai Chionoi. Upon returning to Colombia he beats Manny Elias in front of 20,000 spectators, thus winning the chance to face Brazilian bantamweight titleholder Eder Jofre.

“I’ve many anecdotes from that epoch. It was a whole new world, a discovery of things when I landed the first time in Bogotá to fight Jaime Caro. A city so big, the cold weather, the enormous house where I slept [the hotel], the floor made out of plush fabric [the carpet], imagine, I was used to step on mud, and the little room that took me up and down [the elevator]. When I returned to Chambacú nobody believed what I was saying. The funniest thing I remember is when they invited me to the Presidential House after the fight with Ben Alí. I dedicated the victory to President Guillermo León Valencia, but when I had to do it in person, I forgot his name and I said I dedicate this fight to the man that is sitting over there. Can you imagine the embarrassment?”

“In my opinion, Chionoi was the most difficult rival I ever had. He closed up my right eye and my arms hurt. He hit hard. They proposed a rematch for U$10,000, but if we’re talking about fear, hey, I didn’t want to know anything about that guy! I told Sócrates Cruz, don’t take that fight, let’s get out of here. I drank the soup with a straw, ate smashed rice because I couldn’t move my mouth. In Manila I brought a pair of shoes that lightened up upon stepping, which was a novelty here in Cartagena. I’m gonna be honest with you: Bogotá admired me, they loved Caraballo. Barranquilla supported me, but here in Cartagena people wanted me to lose. Isn’t bizarre?”

The Hour of the Truth Arrives

The boxing county stirred on November 4, 1964, day in which the championship match between Bernardo Caraballo and Eder Jofre was signed. The stravaganza was about to be cancelled due to the high taxes the city of Bogotá wanted to charge Greek promoter Georges Parnassus, but at the end city representatives and boxing entrepreneurs reached an agreement. The highly anticipated match, the historic event for Colombian boxing was a done deal! The bout took place on November 27 at soccer stadium “El Campín” in front of 25,000 spectators. Half of them entered using falsified tickets. Parnassus lost thousands of dollars. Boxing experts said that if Caraballo passed the eighth stanza, he would be the new 118-pound champion.

“That one was the most painful performance of my life. The day of the fight I arrived to Continental hotel at 7:00 A.M., to check my weight, because they installed the scale in that hotel. I weighed 117 pounds, so I didn’t worry about that because the official weigh-in was at 12:00. When I returned five hours later, surprisingly, I weighed 120 and Jofre 118. We argued, but they didn’t listen and gave me two hours to lose the extra pounds. At 1:00 P.M., Sócrates made me wear a plastic sweater and trot up and down the Monserrate mount, but I was still overweighed. So he put me on a sauna and finally I reached the 118 pounds. What they did to me was brutal. When I went to the fight I was already a dead man, so to speak, because my real weight was 115, while Jofre was 120. I was cheated.”

“Jofre hit hard, so hard that in the second round he paralyzed my left leg, in the fifth he slowed me down and in the seventh he caught me with a right to the chin that sent me to the canvas. I stayed down listening to the count because I was exhausted. My legs were too heavy and my wife Zunilda shouted ‘stand up Bernardo, stand up,’ but no way, I was out. For that event I got paid $125,000. That night somebody sent a mariachi to the hotel and they sang that Mexican song that goes like this: ‘porque después de este golpe ya no voy a levantarme/because after this punch I won’t stand up’. That was a very sad night that I shared only with Zunilda and true friends.”

Caraballo’s defeat brought frustration. People called him coward, irresponsible and many other things. The army of flatterers and frogs disappeared because “The Champion” had lost. “Then I knew who my true friends were. I’m grateful to journalist Melanio Porto-Ariza because he always believed in me. He put his hands on fire for me.”

Second chance

Caraballo recovered from the punch, contrary to the song they dedicated to him, and initiated a second stage in his boxing career. He defeeated American Ronnie Jones, Venezuelan Manuel Arnal, Brazilian Valdomiro Pinto, Panamanian Eugenio Hurtado, Mexican “Memo” Téllez, among others, until getting a second championship opportunity, this time against Japanese “Masahiko” Harada, an aggressive fighter who had dethroned Jofre. “I was the topdog for that fight. I must admit Japanese people treated me well and they gave me all what I needed to train.”

The card took place at Tokyo’s Budokan Hall on July 4, 1967 with an attendance of 15,000 Japanese fans. Caraballo, surprisingly, was send to the deck in the first round, “but by the third I’ve evened the fight out and from that point I dominated Harada. Before hearing the decision I was sure the title was mine. I was robbed! That was the fight of my life, very hard. I remember that Harada reopened the only cut I ever had. Five years earlier a Jamaican kid named “Killer” Salomon had cut my eyelid and Harada reopened that. At the end of the fight Harada congratulated me saying I was a very good boxer and he even invited me to a party.” Somehow nostalgic, Caraballo says: “I wasn’t born to become a champion.” Even though the decision of the three judges, two from Japan and the other one from the US, favored the local, Caraballo was received in Barranquilla as a champion. A reply of the video was shown a couple of days later in Colombia and it confirmed Caraballo had been victim of a home-town decision.

Benny’s Things

Bernardo –Benny- Caraballo was eccentric in a certain way. Among his weird things was to step up into the ring wearing three robes. The ritual to take off each one was a show by itself. The inner most was made out of leopard skin, which he still keeps. “That one was a gift from Marcos Hernández, who brought it from Los Ángeles in 1963. I used it the first time against Ronnie De Cost. I used to wear it for big fights.” Benny popularized the word “chichipati” (meaning poor-quality). That was how he loved to call his opponents. Even more, he loved to predict the round in which he would knock his rival out, thus initiating a psychological war before the day of the fight.

The Career Continues

The fight against Harada was followed by a defeat against Mexican “Chucho” Castillo, which did cost him the privileged position in the NBA’s ranking, to where he would never return. People didn’t forgive him and started to gossip about his bacchanals and the way he was spending money. The idol starts to fall. But in February 1968 his pride is on the line when he fights another Colombian idol, topdog Antonio “Mochila” Herrera in Barranquilla. He brutalizes Herrera in four. “I castigated him from the opening bell and didn’t stop punching until he fell apart.”

The unexpected victory made people talk about him, once again. Those are the critical years of Colombian boxing. Great pugilist are eclipsing down, but Caraballo keeps the torch for another ten years, sometimes winning, sometimes losing. It’s an incredible demonstration of willpower. Old and without the qualities that had made of him Colombia’s greatest boxer, Caraballo becomes the boxer that upcoming stars want to fight to show him in their resumes. Promoters and prospects want to make money and fame out of Caraballo’s big name.

Shames

Defeats Víctor Cano, loses to Venezuelan Alfredo Marcano, outpoints twice Mexican David Sotelo, falls to Panamanians “Ñato”Marcel, “Paticas” Jiménez and Mario Molo. Wins the Colombian featherweight title against countryman Miguel Espinosa in Barranquilla, but now it’s quite evident he’s no longer “The Man”. In an effort to keep his name alive, dubious promoters organize “championship nights” selling Bernardo Caraballo against cab drivers as the main event. Result: farce and lie; his image deteriorates. In an effort to support boxing, promoters make bizarre mistakes with Caraballo joining them. Fans don’t want to see him fighting and for the very first time a Caraballo show doesn’t leave earnings.

Retirement

On December 12, 1973 Caraballo faces Alfonso Pérez, winner of a bronze medal at the Olympic Games held in Munich. Cartagena’s “Once de Noviembre” baseball stadium fills its capacity to witness a draw. Then he gets three consecutive knock out victories; a phenomenal win over Panamanian Mario Mendoza; a controversial defeat to Miguel Espinosa; knocked out by Alfonso Pérez and from that point Bernardo Caraballo starts to lose against kids that in his best epoch would not even have the honor to carry the bucked where he would spit. After hanging up the gloves he joined Colpuertos, a Government-run entity created to administer Colombian sea and fluvial ports. Today, and thanks to the job at Colpuertos, he receives a pension and lives a quiet, peaceful life surrounded by his descendants.

Bernardo Caraballo fought 108 times in sixteen years as a pro, winning 84 times, losing 18 with 6 draws. He had 70 non-Colombian rivals, fought in 8 countries and 14 Colombian cities. He had five kids with his wife Zunilda, three boys and two girls. They have left him 16 grandchildren and all of them love soccer, not boxing. “I’m very satisfied with what I did because I opened the doors overseas,” proudly says the man who changed the fate of Colombian boxing.