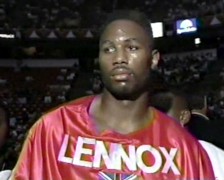

By Andrew Harrison, Safesideoftheropes.com – On the second Sunday in June, Lennox Lewis will be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, headlining the 20th annual ceremony held in Canastota, New York. In doing so, he will become only the fourth* British fighter to receive the honour in the modern fighter’s category (last bout no earlier than 1943).

By Andrew Harrison, Safesideoftheropes.com – On the second Sunday in June, Lennox Lewis will be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame, headlining the 20th annual ceremony held in Canastota, New York. In doing so, he will become only the fourth* British fighter to receive the honour in the modern fighter’s category (last bout no earlier than 1943).

I remember vividly the feeling I had as a twelve year old boxing fan in the spring of 1989, having to watch Frank Bruno put on a brave face and josh with Harry Carpenter moments after being pulverised by Mike Tyson. I was absolutely crushed. Once again the pitiful reputation of the British heavyweight boxer had been underlined, reaffirmed and rubber stamped and as my family carried on with daily life, I could only sit in silence biting my lip. I’d somehow taken the whole thing quite personally, my mood worsening by the minute. Belittled in front of the Americans again, brave to the end but ultimately not good enough, a familiar story ever since Bob Fitzsimmons had held the crown, won by crippling Jim Corbett with a body punch what seemed like a million years ago..

For a kid from a council estate in the bleak North East of England suffering under Margaret Thatcher, there wasn’t much national cheer to be had. To me at that time, America symbolised power and authority within the sport and I hated it. I vowed that I would be the man to right Britain’s shameful reputation and with that, put on my Italian Stallion style sweat suit and galloped around the wastelands close to my home, punching the air until my lungs were fit to burst.

Needless to say, I never quite managed to restore credibility to Britain’s big men (I’d have had to grow a couple more arms and legs to make weight to start with). Thankfully however, Lennox Claudius Lewis rode to the rescue in 1989 and would have quite an influence on me throughout my formative years. It seems we never take fighters to heart in quite the same manner we do during this period of our lives, Lewis will always remain the heavyweight champ I took most personally.

Lewis turned pro at around the time ‘Iron’ Mike was making mincemeat of ‘Big’ Frank and I was haring around my estate recreating Rocky montages. He would appear from time to time as a guest presenter on boxing telecasts, usually making some crass remark on how he’d deal easily with Bruno or Gary Mason, the big two at the time on the British heavyweight scene. My father would tut in disgust, fighters from his day just didn’t behave in the way the post Ali generation did, cockiness in a sportsman was repulsive to him. As my interest in Lewis increased, my father’s disdain for this imported Canadian gathered pace at the same speed.

We settled down to watch the Lewis-Mason British title showdown in 1991 on terrestrial television, both firmly behind Gary (who held a lofty world ranking at this juncture). As the fight unfolded however, my allegiances shifted. I began to see one of our heavyweights flourish before my eyes, whilst my father on the other hand, appeared only to see a cocky imposter tormenting a brave but overmatched slugger (and in his eyes, a ‘true’ Brit). Lewis was what I’d been waiting for, whilst Mason rather fitted the mould of the battling domestic heavyweight my father had been brought up on.

I was firmly on board from that day onward as Lewis bulldozed Mike Weaver, crushed Glenn McCrory and battered a shot and tired looking Tyrell Biggs. He polarised the difficult relationship my old man and I shared at that particular time; dad would take the opportunity to rubbish Lennox at every turn and remind me that I didn’t yet share his knowledge of the fight game, or anything else come to that. He’d never have beaten his idol Bruce Woodcock I’d be informed, he was far too amateurish and he’d sure as hell never win the title that’s for sure.

It was Halloween 1992 when Lewis exploded onto the world scene with the mind scrambling knockout of Donovan ‘Razor’ Ruddock in London. With Mike Tyson behind bars in Indiana, Lennox Lewis suddenly became the danger man of the heavyweight division. Pencilled in to fight either, former stoppage victim from the ’88 Olympic final Riddick Bowe or the increasingly vulnerable looking Evander Holyfield for the undisputed heavyweight title, Lewis’s coronation looked a certainty.

Lennox however, was to about to become firmly acquainted with the politics of modern day boxing. Title belts in London rubbish bins, failed agreements and public feuding would see him largely frozen out and kept away from the undisputed championship, long since established as a strictly American province. Awarded the WBC version by default, the linear heavyweight crown would pass from Holyfield to Bowe and back again as Lewis (seen very much as a background player in the States) was left to defend against Tony Tucker and Frank Bruno, his reputation and skills floundering as his career stagnated and appeared to go into reverse.

The ascension to the throne of a British heavyweight for the first time in almost a century, something which had seemed inevitable, was now starting to look as if it might never materialise. Holyfield would lose to Michael Moorer, who’d again promise Lennox the next dance, only to allow George Foreman to cut in and waltz off with the belts.

Despite this rejection, Lewis marched on stoically towards what he assured us was his destiny. In 1994 and with Moorer looking to fight Foreman, it seemed he’d at least get a chance to take out his frustrations on loathed rival Riddick Bowe whilst he stood in line, once he’d taken care of a mandatory assignment against the tough but largely unheralded Oliver McCall. Lennox, perhaps with one eye fixed on Bowe, fought like a novice against McCall and walked into the sucker punch which threatened to derail his career, much to my old man’s obvious delight.

It was a long day indeed the Sunday which followed, riding the ribbing he gave me whilst hanging onto every news bulletin, hoping childishly that the controversy which raged over the quick stoppage, would somehow give Lewis his title back. Every report featured a gormless looking Lennox, dazed, confused and sucking on an ice cube due to the fat lip McCall had given him (which matched perfectly the pet lip he’d given me).

Lewis had succumbed to overconfidence, ego and arrogance. As talented as they come, his lax approach looked to have shelved him in the ‘coulda, woulda, shoulda’ category and I identified fully. Fairly gifted academically yet inherently lazy, the obituaries written on Lennox’s career looked awfully similar to my school reports. Lewis’s return not only put the record straight for those quick to write him off as a fighter, it taught me that being good at something and arrogant with it, didn’t amount to a hill of beans if you didn’t graft to actually achieve something.

With Emanuel Steward now at the helm, Lewis began to improve and show flashes of talent I’d rarely seen before in a heavyweight. After the dry run he was now going about his business in the correct manner, only now he faced more doubters than ever. Lennox steadily began to find his identity as a fighter; a punch perfect shift against Tommy Morrison and a gut check performance at Madison Square Garden, against a fiercely tenacious Ray Mercer put him back on track. Lewis gained revenge over McCall in regaining the WBC title in 1997, defending against Henry Akinwande in farcical circumstances before coming full circle and destroying the feared Andrew Golota in much the same blistering form he’d exhibited when wrecking Ruddock years previously.

Lewis was again the heir apparent, thumping linear champion Shannon Briggs in a pleasing slugfest the following year. America however, still refused to accept Lewis as the true heavyweight champion, electing instead to focus on Mike Tyson’s conqueror, WBA and IBF champion Evander Holyfield. In 1999 Lewis was finally given the opportunity after 10 years as a professional boxer, to become the undisputed heavyweight champion. Seemingly robbed in the first encounter with Holyfield (declared a controversial draw), the mission as he termed it, was finally achieved later that year in the rematch, which Lewis oddly took via unanimous decision in what had appeared a much closer fight.

After Holyfield, Lewis became a far more animated performer, the shackles now finally off. Now in his prime, he dealt with challengers Michael Grant, Frans Botha and David Tua in emphatic fashion before unbelievably succumbing to the sins he’d committed against McCall. Hasim Rahman knocked Lewis cold in South Africa, ripping away his championship and with it, any chance it seemed of a lasting legacy. After everything he’d been through it looked as if he’d gone and thrown it all away.

Not so it would prove. Lennox would again rise from the ashes of embarrassing defeat and go on to dabble with greatness. In perhaps his finest performance, he rebounded to outclass Rahman, knocking him cold with a perfectly executed one-two in round four, punctuating a flawless exhibition. A faded MikeTyson would fall next, further strengthening Lewis’s reputation. They were fights my father and I would watch together again, the old man now with an obvious respect for my man, no longer the cocky amateur, rather now a great fighter at the rum old age of 36.

In his final fight, a seemingly shot and out of shape looking Lewis tussled ferociously with Vitali Klitschko in perhaps the last great fight we have seen in the blue riband division. Lewis pulled it out of the bag somehow and both he and I breathed a huge sigh of relief. The show was finally over.

It was a hell of a journey for a Lewis fan, the big man battling through frustration, adversity and setbacks to become arguably Britain’s greatest fighter of all time.

Lewis follows Jack ‘Kid’ Berg, Randy Turpin and Ken Buchanan as Britons inducted into the Hall from the modern era.

* Please note Barry McGuigan is Irish, despite attaining British citizenship and winning a British title.